An Employment Miss

August's jobs report came in weaker than expected. But there are some bright spots.

Note: any and all opinions are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cleveland Fed, the FOMC, or any other person or entity within the Federal Reserve System. I am speaking exclusively for myself in this post (as well as in all other posts, comments, and other related materials). No content whatsoever should be seen to represent the views of the Federal Reserve System.

How foolish was I to schedule a follow-up quantitative-easing related post on the day of a jobs report! I was expecting, as most were, a much stronger jobs report than the one we got today. Instead of that post (stay tuned for it next week!), I threw together some charts to put today’s number in context.

As always, there’s good news and bad news—let’s get the bad done and over with.

The Bad News

August’s payrolls indicated that 235,000 jobs were added last month. On one hand, 235,000 jobs is a lot of jobs in historical context. Between 2011 and the pandemic, the U.S. economy added 197,000 jobs each month, on average. But on the other hand, that number came in far below most expectations. June and July boasted around a million new jobs each month, which combined is nearly enough to make up for a full years’ worth of job growth.

The hope was for this trend to continue, even if not at the same extreme magnitude. Instead, August’s data indicated that it was the second weakest month of job gains in 2021, behind January’s 233,000.

This led to a less-significant decline in the working age unemployment rate and headline unemployment rate than anticipated. The unemployment rate dropped to 5.2%, while working age unemployment fell to 22% as the working age employment rate rose from 77.8% to 78%.

In this sense, this unemployment report was a disappointment. We were all, hopefully, hoping for a better report. Chair Powell, in his Jackson Hole speech, indicated that the Fed was anticipating stronger job growth in the coming months. Further, he said:

I was of the view, as were most participants, that if the economy evolved broadly as anticipated, it could be appropriate to start reducing the pace of asset purchases this year.

Will this jobs report lead to a readjustment of the Fed’s outlook? Today’s report does not seem to be the one they were hoping to see before their meeting later this month. Does this postpone tapering? Was this a one-off miss? We’ll get the answer to the first question later this month, but now we have another month to go before we can know the answer to the second.

The Good News

On the bright side, long term unemployment is subsiding. 39.3% of the unemployed had been unemployed for greater than 27 weeks in July; in August, this number fell to 37.4%. This wasn’t as large a decline as in prior months, but nonetheless 246,000 people who were unemployed for longer than 7 months are no longer unemployed.

There’s still a very long way to go here, but any decline in long term unemployment is good news. Short term unemployment is inevitable, but long term unemployment is bad. Long term unemployment leads to hysteresis and, with unemployment benefits expiring next week, difficult lives.

Additionally, a growing share of the unemployed are those who are re-entering the labor force after having stepped out of it earlier in the pandemic. Those permanently unemployed, while still a large share of unemployment, are starting to make up a smaller portion of the total unemployed.

The reduction in unemployment can best be seen in levels. August brought more people into the labor market as temporary unemployment declined and permanent unemployment did not increase.

Further, the prime age employment rate has recovered remarkably faster than in previous recessions. Today’s report indicated a slower recovery rate than in July, but this is nonetheless not your parents’ recession.

What Now?

This jobs report should definitely make the Fed a bit more cautious on when to begin tapering. Given the amount of space between FOMC meetings, tapering was unlikely to begin until around the end of the year, sometime between November and next January. September’s jobs report will show if August was a fluke or a new trend. November’s FOMC meeting should be quite interesting.

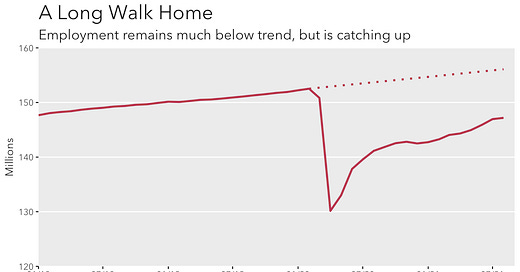

In any case, the economy remains 5.3 million jobs short of the level it had before the pandemic, and this is without considering where we might have been had there been no pandemic. It is absolutely critical that the Federal Reserve maintain an accommodative stance until maximum employment.