Note: any and all opinions are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cleveland Fed, the FOMC, or any other person or entity within the Federal Reserve System. I am speaking exclusively for myself in this post (as well as in all other posts, comments, and other related materials). No content whatsoever should be seen to represent the views of the Federal Reserve System.

Perhaps more than during prior bouts of quantitative easing, there has been a lot of concern that the Federal Reserve has been monetizing the debt. In this post, I will explain what that means, see if they really are, and discuss why they are not really doing so in any meaningful way. The Fed’s independence should be a treasured and protected thing, so the answer to this question is important.

What is debt monetization?

Debt monetization traditionally refers to when a central bank finances public debt through the permanent creation of non-interest paying money. That is, it’s not term-based; it should be a permanent increase in the monetary base to finance government debt. Even more precisely, some intent of creating inflation should be involved in order to really count.

Commentators often stray very far from this definition. Many argue that the Fed is monetizing the debt any time it buys any Treasury security. As will become apparent, I disagree with this definition. Of course, from its inception until 2008, the Fed used to set monetary policy primarily through open market operations of buying and selling Treasury securities, but few ever accused the Fed of monetization then. However, since it is so common to do so in the mainstream, I will use “monetization” a bit more broadly to cover three general ways in which a central bank could monetize the debt.

In option one, the loud and heavy option, the central bank can straight up buy debt directly from the Treasury, hot off the presses. This is traditional, old-school monetization—new money is created right there on the spot. This has been illegal in the United States since 1935, though, as we’ll see, there wasn’t a permanent total ban on this until 1981. This may sound similar to quantitative easing, but it’s not really—the Fed is buying assets that have already been bought and creating interest bearing reserves in the process.

In option two, the backdoor option, the central bank monetizes the debt through remittances to the Treasury. The Fed has sent its leftover profits to the Treasury after paying its own bills since the late 1940s. The System Open Market Account, which holds the security holdings of the Federal Reserve, does in fact own a lot of securities, essentially all of which are fixed-income. This generates quite a bit of revenue for the Fed. The profits get sent to the Treasury and help finance the debt by cancelling out interest payments.

A third option would be something like yield curve control. Under yield curve control, the central bank targets specific yields across the yield curve and commits to maintaining them, through monetization if necessary. This is of great benefit to the Treasury, as it essentially guarantees (often favorable) costs of borrowing money.

What isn’t debt monetization?

Though I am accepting a broad definition of monetization, I can’t accept every accusation of monetization to be monetization.

I have often heard the argument that even though quantitative easing isn’t printing money for the Treasury, it still enables huge deficits by guaranteeing the purchase of government debt. In other words, since primary dealers know that the Fed will buy $80 billion in Treasury debt from them, they’re more willing to bid at lower rates—or even bid at all—at Treasury auctions than they might otherwise do, since they know that they’ll more or less be reimbursed soon after the purchase. This is seen as enabling large deficits, and therefore as monetization.

That may be true, but this is not what monetization is. The private sector is still the one purchasing the debt, and it is not permanently increasing the monetary base in doing so. Sure, the government benefits from borrowing at lower interest rates, but they are not meant to be the main beneficiaries of lower yields. Given that some prominent voices in Congress, like Joe Manchin, would actually prefer that the Fed didn’t do quantitative easing, I’m not sure that Congress sees quantitative easing as an easy way to finance large deficits. I do not find the claim that Congress would avoid deficit spending without large scale asset purchases convincing—it never stopped them before 2008! And if the concern is that low interest rates encourage fiscal spending, do high interest rates discourage spending? If the concern is that the Fed is overly accommodating fiscal spending, why would the solution be to arbitrarily punish fiscal spending? Each time interest rates have been low, was the Fed accommodating fiscal spending? I don’t see a strong argument to be made there.

In any case, there are reasons to be doubtful that the “quantitative easing enables large deficits” story is even that accurate.

First, quantitative easings’ power seems to come more from forward guidance than the actual asset purchases themselves. Consider the fact that the ten-year Treasury yield rose during most of QE3 during the notorious “taper tantrum”, a result of negative forward guidance from then-Chair Bernanke. When inflation concerns first started to gain traction early in the year, a seven-year note auction in February went poorly, with yields jumping above the then-prevailing market rate. In the 2011 and 2013 debt ceiling crises, short term Treasury yields jumped several basis points. Quantitative easing is thus no guarantor of lower interest rates; it’s not yield curve control.

Of course, we don’t know the counterfactual (i.e. where yields would have been if the Fed had issued forward guidance committing to lower rates but did not buy securities), but the only finished QE program that left long term yields lower than before it began was QE2 (sorry for that chunk of the graph being tricky to read—QE2 ends in late June 2012 and is soon followed by the beginning of QE3 in September). So long as the Fed targets inflation, an overly expansionary fiscal policy would still result in higher interest rates.

Second, primary dealers are not even the primary purchasers of debt. According to the chart borrowed from Bloomberg below, primary dealers have been buying roughly 30% of new debt, and in fact they have bought a smaller share since the pandemic and quantitative easing began, edging down to 20%. In comparison, investment funds (a wide definition, but surely includes pension funds and the like) buy between 50% and 75%. Investment funds bought a smaller share of the debt during the onset of the pandemic, similarly in the face of quantitative easing. The rest of the issuance got picked up by foreign and international investors, from whom the Fed does not buy in quantitative easing. In any event, primary dealers are required to submit “reasonably competitive” bids at Treasury auctions—they don’t really get a choice to simply “not” buy the debt.

Increased reserve balances likely do lead to an increase in demand for Treasury debt, as financial institutions try to shed excess liquidity by buying higher-yielding assets. As such, money market funds have increased their demand for T-bills, and banks have increased their demand for longer-term securities. But this isn’t monetization!

Third, in a safe asset shortage world where there is such a large demand for safe assets like Treasury debt, do we really think there would be fewer buyers without quantitative easing? Or consider institutional demand for Treasuries given regulatory pressure—would they not buy these securities anyway? Is anyone suggesting that there is weak demand for US debt? I find that unlikely. As seen above, investors have bought quite a bit of the Treasury’s debt in the last year. Each category’s share of debt purchases has been more or less constant through quantitative easing.

Fourth, the public increased their holdings of Treasury debt by double the dollar amount of the Federal Reserve since the pandemic began. Consider that 80% of outstanding Treasury debt is not held by the Federal Reserve. Let’s imagine that quantitative easing is true monetization. In that case, the Fed is only “monetizing” 20% of the debt; or, in other words, 80% of the debt is not monetized. Even in that false scenario, I don’t find that to be serious monetization.

Fifth, reserves are interest-bearing money. Back in the day when reserves paid no interest, banks had very little interest in holding any reserves past the required amount. If a bank wanted to reduce its holdings of bank reserves created through the purchase of Treasury debt, it could increase its lending activities in an attempt to drain its reserves. Of course, this cannot work in aggregate, since somebody has to hold the banking system’s reserves, but this wouldn’t stop any one bank from trying anyway. Increased lending would raise aggregate demand and put upward pressure on the price level—creating inflation that also helps to monetize the debt. In a world without IOR, monetary base injections—like QE—would be more inflationary, but that’s not our world.

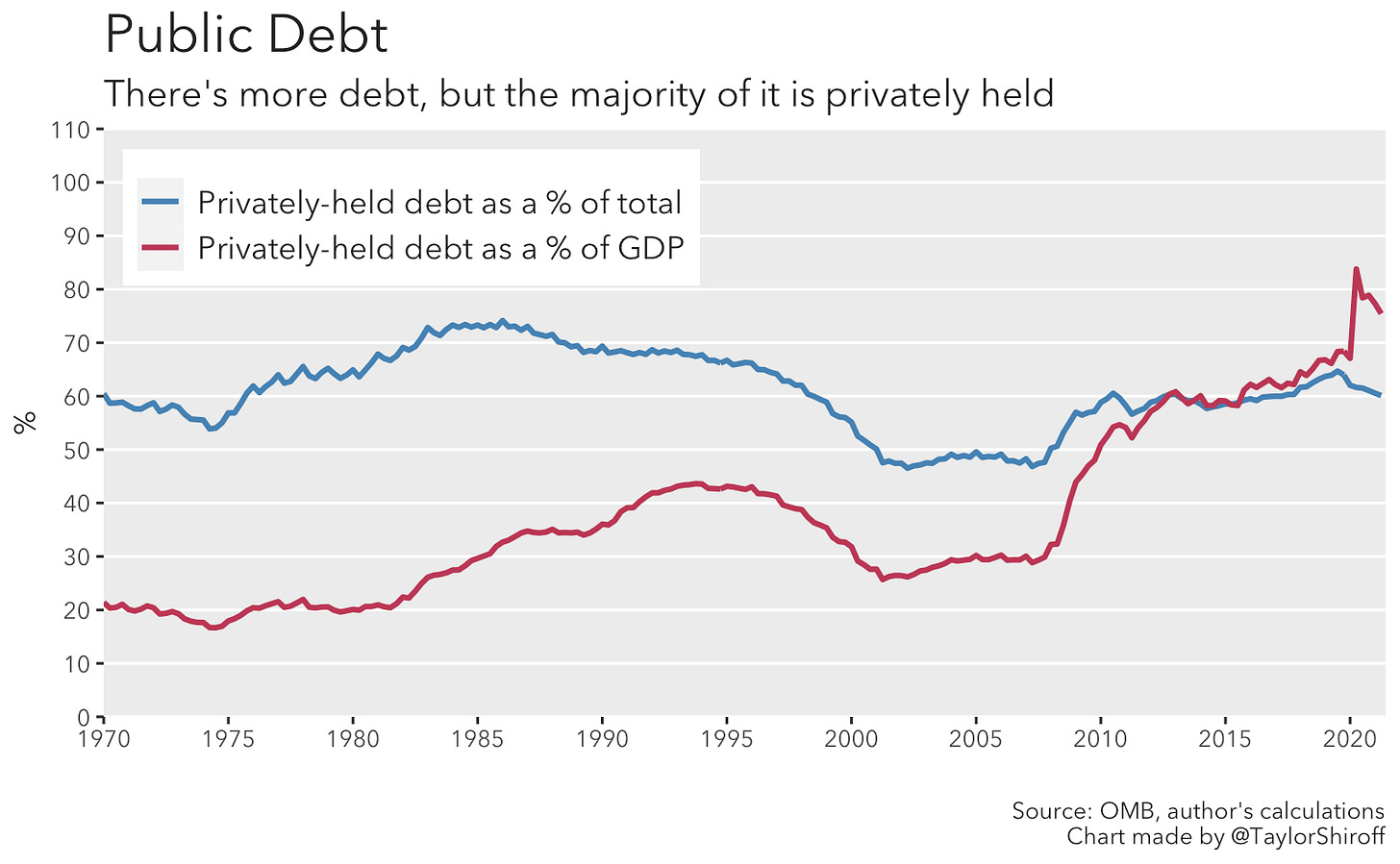

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, an important consideration is whether the Fed will hold securities forever. If the Fed plans on eventually letting securities mature off of their balance sheet or selling them back to the private sector, the increase in the monetary base created during quantitative easing will be undone. The private sector will be forced to hold the debt, and the reserves created when it was bought will be destroyed once it is sold. This will leave the public holding a similar share of the debt as before quantitative easing. The Fed got close to its pre-Great Recession share of Treasury holdings by 2019, nearly undoing the entirety of QE3. Below we can see that since around 2009, roughly 60% of the debt has constantly been held by the private sector.

Considering these four points, I do not think that quantitative easing directly or through “enabling large deficits” or “ensuring demand for Treasury debt” is monetization by definition, or even by twisting the definition.

A brief history of American debt monetization

Now that we know what monetization is and is not, we can move toward America’s history with it. America only permanently established a functional central bank in 1913 with the Federal Reserve Act, so we’ll pick up the story there. This paper from the New York Fed is a good resource.

World War I broke out the year after the Federal Reserve Act was passed, and in 1917 the United States became involved in the conflict. The Treasury was quite intent on using the Fed to raise (create) money for the war effort, and sold the Fed $50 million in bonds at a rip-off interest rate. Unamused, the Fed did not volunteer again to buy debt during World War I, something that made the United States significantly different from many of the other participants in the conflict.

The Fed did, however, make cash management loans to the Treasury, which were essentially super short-term Treasury debt, often with a maturity of less than a week. These were designed to handle short-term Treasury cash needs; say, tax day was very close, but the Treasury needed just a little to keep things going. As this wasn’t free money to the Treasury (the Fed was repaid), it wasn’t truly debt monetization, but it was still nonetheless an erosion of the Fed’s independence and a cousin of debt monetization.

Nonetheless, the amount of currency in circulation had doubled after the war, which led to a near doubling of the price level between 1914 and 1918. Inflation is another way a central bank can make a nation’s debt manageable without literally monetizing it.

The Fed continued to make cash management loans after the war ended, continuing to provide the Treasury with short term loans through the 1920s. This changed with the Banking Act of 1935, written under Marriner Eccles’ influence. The Banking Act did many things: it created the Board of Governors, made the Chairman the head figure of the Fed, centralized power in DC, and edited Section 14 of the Federal Reserve Act to make direct purchases of Treasury securities from the Treasury illegal.

This prohibition on direct purchases lasted for 7 years, until the United States became involved in World War II and Congress modified the change in Section 14. Then-Fed Chair Eccles suggested that the Fed should be able to buy debt directly, and maybe even underwrite Treasury debt:

“It might be that the market would be such that it would be difficult to float the

necessary amount of securities at a particular time, in which case the Federal Reserve could take a portion of such securities and, later, could sell those securities. In that case the Federal Reserve would attempt to redistribute those securities. It would underwrite an issue and undertake to redistribute it when the market was favorable.” — Marriner Eccles in early 1942

This ultimately is what became the new law. The Fed could buy Treasury securities right from the Treasury, but they could only hold up to $5 billion in directly-purchased debt at any time. This was meant to be temporary for during the war, but was extended until 1950. This exemption was extended again, and again, and again, until 1981.

The Fed also did yield curve control during and after World War II. The Fed would need to step in to Treasury markets to buy debt both in the way Eccles described above and in secondary markets to keep yields below their ceilings. This kept the interest payments on the debt reasonable, especially considering the inflation that occurred during this period. Yield curve control was progressively discontinued after the war and permanently terminated after the Fed-Treasury Accord in 1951. An under-appreciated fact, though, is that World War II was largely funded by taxation and debt issuance and not by money creation.

The Fed nonetheless often held billions of dollars of directly-purchased Treasury debt at any point during World War II. With all the Fed’s accommodations, the amount of currency in circulation in 1945 was roughly five times its level five years earlier. Between the end of the war and 1981, the Treasury continued to infrequently borrow from the Fed, though sometimes in great amounts.

When Congress refused to raise the debt ceiling in 1953, the Treasury came up with a clever work around. The Treasury issued $500 million in gold certificates (backed by Treasury holdings of gold) and used these certificates to buy $500 million in soon-maturing debt from the Federal Reserve. In effect, the Treasury created its own money, and swapped out Treasury debt for gold certificates on the Fed’s balance sheet. In a flexible definition, this was a form of debt monetization done by the Treasury itself. Of course, the Treasury can’t just issue trillions in cash to buy back the rest of the debt, though.

By the late 1970s, the Treasury began to issue cash management bills rather than borrow from the Fed. This meant that the public could finance the Treasury’s short term cash needs rather than the Fed. Around this time, Congress, the Fed, and the Treasury all sort of collectively realized that the Section 14 exemption was not really necessary anymore. And that’s the end: there has not been a single purchase of Treasury securities hot off the presses since 1979, and this has been explicitly prohibited since June 1981.

So, is it true?

By now, it should be clear that the Fed is in absolutely no way buying freshly printed debt hot off the presses, so that form of monetization is off the table. The Fed is also obviously not engaging in yield curve control. Sure, through large scale asset purchases they are indeed trying to lower longer-term yields, but the market has proven willing and able to resist this. However, there is some truth in the fact that the Fed’s remittances do help finance the debt, as it reduces the Treasury’s net interest payments. It’s more of a backdoor monetization, and is not true monetization by definition, but it is real.

The Fed earns quite a lot on its portfolio of securities—between $100 and $120 billion since 2014. After paying interest on reserves and all the Fed’s other expenses, the Fed is left over with a large amount of net income. Nearly all of this income winds up going back to the Treasury as more or less free money to them. This money can be seen as cancelling out some amount of the Treasury’s interest payments on its debt.

We can refer to the portion of the Treasury’s net interest expenditure on the debt that is covered by Fed remittances as the “monetized share”. It is, after all, more or less money going to the Treasury that, if not for the Fed, would not be going to it. This isn’t because the Fed is printing money for the Treasury, but rather because the Fed printed money to buy an asset whose income streams circle back to the Treasury only by virtue of belonging to the Fed’s balance sheet. Of course, this isn’t really monetization, but again it gets at the point that the “everything is monetization” folks worry about—that central banks are getting a bit too close to the Treasury.

In 2020, the Fed’s remittances covered around a quarter of the Treasury’s net interest payments. The “monetized” share’s peak in 2015 was not entirely due to remittances from the Fed’s income, but rather occurred as a result of a legal requirement to transfer excess capital from the Fed to the Treasury. True, the Fed’s transfer payments covered a progressively larger share of the Treasury’s net interest payments from 2009 through 2016, but by 2018 and 2019 the share returned to its historical average—until the pandemic.

There is, of course, a relationship between the Fed’s share of the total outstanding debt and the amount the Fed sends back to the Treasury. The Fed acquired more debt than ever before by the end of the Great Recession quantitative easing programs, which led to a large increase in remittances. However, despite nearly doubling its holdings of Treasury debt from 2019 to 2020, a magnitude of trillions, its remittances to Treasury increased by only $30 billion:

This increase in the Fed’s remittances to Treasury is largely due to the drastic cut of the interest rate on reserves. In 2019, the Fed paid out around $35 billion in interest payments on reserves; in 2020, only $8 billion.

The monetized share is currently a small amount of the Treasury’s total annual interest expenditure. Sure, the Fed sent over roughly $80 billion to the Treasury in 2020, but this only covered 14% of the Treasury’s net interest expenses. In other words, the Treasury had to finance the remaining 86% in some way other than the Fed.

An important point is that remittances will fall when the interest rate on reserves rises, as can be seen in the dramatic 50% decline in remittances from 2015 to 2019. When the time comes to raise the interest rate on reserves, remittances will fall, and the monetized share will fall too.

This will especially be the case if the Fed were to shrink its balance sheet not just by allowing securities to mature, but by actively selling them, too. When these securities reenter the private sector, the interest paid on them—and, importantly, their principal payments—will head to the private sector, not the Fed, and not back to the Treasury. The free lunch will become less free.

Conclusion

By strict definition, the Fed is not monetizing the debt. It is creating interest-bearing money by purchasing Treasury debt second-hand from primary dealers and their clients. Further, the Fed’s purchases are not intended to be permanent—the Fed has shrunk its balance sheet in the past and will surely want to at some point in the future. Finally, the Fed’s purchases are not designed to finance the government nor to increase the price level; instead, they are conducted to support the flow of credit to households and businesses.

Using more flexible definitions, it still doesn’t really look like the Fed is monetizing the debt. The Fed is by no means buying debt directly from the Treasury—this is illegal, as I discussed above. The Fed is also not doing any form of yield curve control. Sure, quantitative easing’s forward guidance channel helps keep longer-term rates lower, but this is not binding.

The best case pops up under the case of remittances. Remittances have made up a larger and larger share of the Federal Government’s net interest payments as the Fed’s balance sheet has grown. That being said, in 2019 only 15% of the Treasury’s net interest payments could have been canceled out by the Fed—in other words, 85% had to be covered from some other source. This rose to 25% in 2020 with the pandemic, but there is no reason why this number cannot fall again.

Some worry that as remittances decline (and the “monetized” share declines with it), Congress might try to find ways to generate revenue from the Fed. True, they have sucked out capital from the Fed before. However, the “monetized” share has generally been below 20% historically. Congress will deficit spend without too much regard for how to pay for it.

The Fed is not printing money for the Treasury. Or, in technical terms, the Fed is not permanently increasing the monetary base to finance the Treasury. This has been completely prohibited since 1981. Nor does the Fed seem to be enabling large deficits, so long as it maintains a credible inflation target. Large deficits as a percentage of GDP are not new, but quantitative easing is.

I’m not sure which debate makes me want to rip my hair out more—the inflation duration debate, the Fed inequality debate, or the monetization debate. Maybe returning to the gold standard and abolishing the central bank doesn’t sound too bad….*