Money Printing: Quantitative Easing and the Abuse of a Term

Does the money printer really go brr?

Note: any and all opinions are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cleveland Fed, the FOMC, or any other person or entity within the Federal Reserve System. I am speaking exclusively for myself in this post (as well as in all other posts, comments, and other related materials). No content whatsoever should be seen to represent the views of the Federal Reserve System.

More than a decade on from its initial use by the Federal Reserve to fight the Great Recession, quantitative easing continues to be misunderstood. In this post, I will discuss how QE is 1) not the same as printing money, 2) not the same thing as monetizing the debt, and 3) not really that inflationary.

Quantitative Easing Definition

I briefly mentioned quantitative easing as one of the 4 main causes of the safe asset shortage in an earlier post, Balancing Fiscal Sustainability and Safe Assets. But what is quantitative easing? By quantitative easing, I am referring to what the Federal Reserve calls Large Scale Asset Purchases. For over a year now, the Open Market Desk at the New York Fed has followed these directions from the FOMC:

Increase the System Open Market Account holdings of Treasury securities by $80 billion per month and of agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) by $40 billion per month.

In large scale asset purchases, what is commonly referred to as quantitative easing, the Federal Reserve buys enormous quantities of some type of security; in the U.S., we have stuck to Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. These securities are bought from primary dealers, who in turn get reserves that pay interest. The goal is some mix of lowering the yields on these securities, boosting the demand for them, shifting how private sector portfolios balance between different assets, removing duration, and money supply expansion, all in order to boost lending and investment in a depressed economy.

What Quantitative Easing Does Do

I am not arguing that quantitative easing has no effect on the money supply, nor any effect on macroeconomic aggregates. Quantitative easing can increase the money supply, if it compels banks to shift asset allocations in their portfolios. But, to cite an oft-cited article, bank lending is a big driver of money creation in the modern economy. Deposits are created by lending — and lending doesn’t require reserves (be on the lookout for a future post on this!). Bank lending can support economic expansion and growth, which itself can also lead to inflation. The issue is that banks just don’t lend like they used to, perhaps due to interest on excess reserves.

Quantitative easing does affect the economy through the credit channel, the financial accelerator, and supporting household income (and therefore aggregate demand). My point in this article is simply to argue that quantitative easing is not the same as arbitrarily printing money, nor is it monetizing the debt, and nor is it inherently inflationary.

Quantitative Easing Is Not Printing Money

When the pandemic first struck, the Fed was swapping up to $75 billion in Treasuries for cash every day. For comparison, as I mentioned earlier, the Fed is currently buying $80 billion per month. Why is this not alarming?

Quantitative easing involves swapping out a high duration asset (Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities) for a zero duration asset — cash. The net amount of wealth of the asset holder and the economy is essentially unchanged. When the Fed buys their $80 billion per month of Treasuries, they are swapping $80 billion of Treasuries for $80 billion in cash. Nobody is any “richer” or “wealthier” in any meaningful way.

This isn’t a perfect comparison, but when an individual decides to sell stock they hold, they are no richer the second before they sell the stocks than the second after. If the only possession to their name is $100 of stock, then at t-minus one second to sale their wealth is $100, and at t-plus one second after sale their wealth is $100.

The difference between holding securities and holding cash is that, theoretically, you don’t want to hold that much cash because cash doesn’t earn anything itself. You should prefer to take that cash and invest it in other stuff.

If quantitative easing were equivalent to printing money, there would be no swap. Net wealth would increase. This would be equivalent to getting to keep both your $100 in stocks while also receiving $100 in cash. In that case, you are actually richer than you were before.

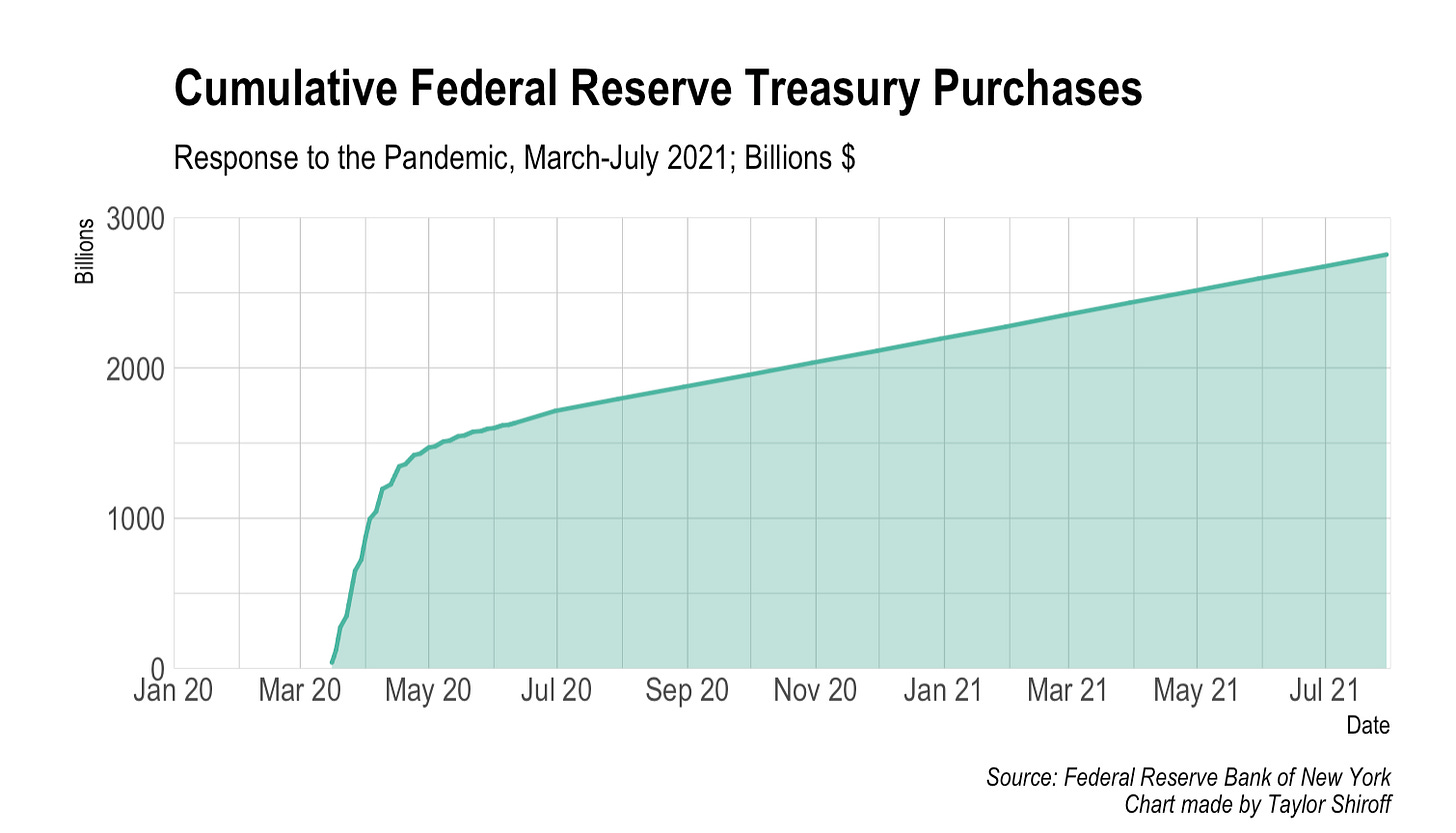

Since March 2020, nearly $3 trillion in Treasuries has been purchased by the Federal Reserve. This should be interpreted as $3 trillion in higher duration assets being swapped for a zero duration asset: reserves held at the Fed. We can see this in the year-over-year percent change in the two components of the monetary base, currency in circulation and reserves:

Currency in circulation has grown, but most of the growth in the monetary base came from a massive increase in reserves. This can be seen super clearly when looking at the raw numbers, shown immediately below, and in reserves as a percent of the monetary base, shown below that.

So most of the reserves generated by quantitative easing are actually just sitting in reserve accounts anyway. Some, including David Beckworth (thanks for the retweet!), have argued that interest on excess reserves has slowed economic growth and likely dampened inflation by keeping money held up in reserve accounts instead of being transmitted into the economy. Whether this is true or not (and it’s debatable), this newly-created money is not transmitted into the economy, and therefore not that equivalent to money printing. Fawley and Neely (2013) show this by comparing the monetary base to M2 measures in four economies:

M2 hardly moved compared to the monetary base.

Reserves at the Fed are a special form of money only banks generally get to enjoy use of. In an excess reserves regime, it has no immediate bearing on the money supply available to us ordinary Americans.

So quantitative easing is not really money printing in the popular understanding of what money printing is: it’s not money for nothing. Therefore, it isn’t likely to be an inflationary hyperdrive. But here is another way in which quantitative easing could be inflationary — if it is being used to monetize the debt. However:

Quantitative Easing Is Not Monetization

Monetization of the debt is when the central bank purchases debt directly from the government, or just skips the hard part and directly lends money to the government.

There is a subtle difference between monetization and quantitative easing: in monetization, the Fed is the first buyer, while in quantitative easing, they are not. When primary dealers purchase Treasuries at auction, they do so with pre-existing money, or money that is available in exchange for wealth they already held. When the Fed steps into the role of a primary dealer, it creates money out of nothing in order to pay for the Treasuries. That could be quite inflationary, and would throw out the hard-won independence of the Federal Reserve.

Think of how quantitative easing normally works: swapping Treasuries for reserves. If the Fed buys Treasuries hot off the presses and credits the Treasury General Account with $80 billion in reserves, that’s $80 billion in new money. The Fed would have become Congress’ credit card, without ever really needing to be repaid as they could repay with borrowed money.

Monetization is not a game that we should want to play, as it messes with the Federal Reserve’s political independence. But, good news: quantitative easing is not debt monetization.

In the current system, primary dealers purchase Treasury debt at auction, and then this debt is purchased by the Federal Reserve. Some claim that confidence in the assumption that the Fed will then buy the debt from primary dealers is about the same thing as monetization. It’s not. The Fed is not reimbursing primary dealers for buying debt at auction. That would be the same as the example above where we sold $100 in stocks: we don’t wind up with $100 in cash and the $100 in stocks. The primary dealers get reserves, but the Fed gets the assets. Nobody is any richer. Dealers aren’t any wealthier than they would’ve been otherwise. In reality, primary dealers are holding fewer Treasuries than before the pandemic, which shouldn’t be a surprise considering what this article is about.

This isn’t to say that the Treasury doesn’t benefit. Because the Fed keeps swapping Treasuries and agency MBS for reserves, primary dealers might keep going back and buying more Treasury debt than they would otherwise. However, this isn’t monetization, and this is by design. This ability further helps keep interest rates low by boosting demand for debt. And when the Treasury needs to issue large amounts of debt in a crisis, as it did in the past year, that demand might not be so strong without easing. Though again, one has to question how much this is really happening due to the incentive (IOER) to keep cash in reserves.

Quantitative Easing Is Not That Inflationary

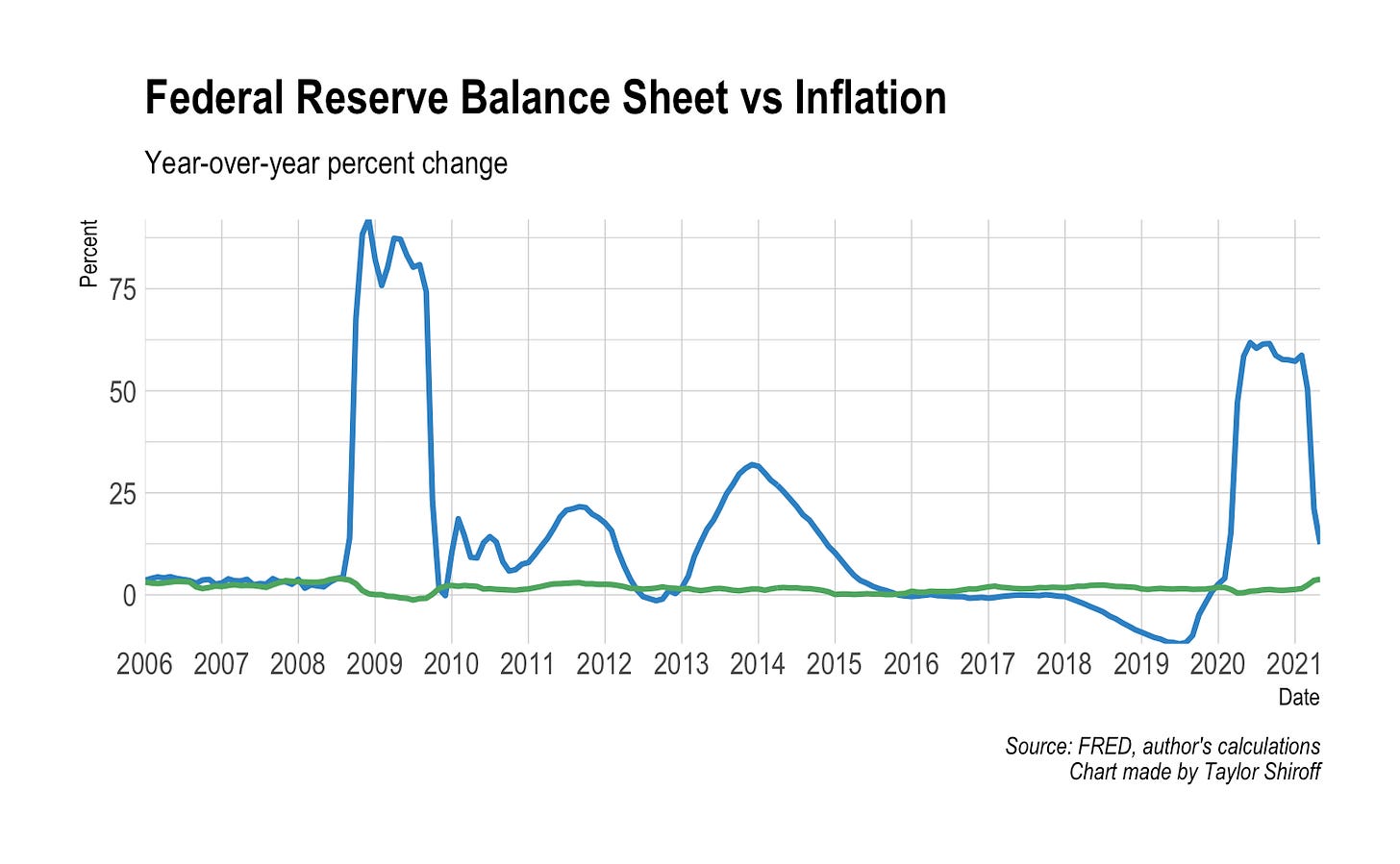

Quantitative easing also can’t really be that inflationary. I’ve already discussed a few reasons for this: it’s not really money printing but a swap of assets, the reserves created by it tend to sit at the Fed, and it’s not monetization. But if that’s not enough to convince you, there’s an obvious third reason: look at inflation. It’s time for a funny graph:

I don’t even have to label it — it should be clear which line is which. We can see QE1 through QE3 on here quite clearly, and the modern phase of QE as well. That green line isn’t a poorly drawn x-axis, but rather PCE inflation. Despite the 4.5 bursts of quantitative easing over the last decade, PCE inflation has still averaged 1.7% since 2006. Fed balance sheet doomers and truthers can continue coming up with all kinds of doom-forecasting measures like the “S&P 500 to Fed balance sheet ratio”, but the rest of us in reality are still waiting for hyperinflation.

Again, this doesn’t mean that quantitative easing does nothing. Research has found that it stimulated investment, reduced corporate bond spreads and supported corporate bond issuance around the world, all of which would promote employment and growth. It likely did help soften economic impacts. Low inflation is more the result of slowing productivity growth, an aging population, and as discussed in my last article, the safe asset shortage. These are all heavy deflationary pressures that quantitative easing is not able to really do much about (in fact, if anything, it helps worsen the safe asset shortage).

Quantitatively Easy Money

Before concluding, I would like to remind everybody that interest rates are a poor measure of the stance of monetary policy. So is the rate of growth of the money supply, whether of the monetary base or of M1 through M4. A better indicator is the growth rate of the velocity-adjusted money supply, or nominal GDP. Huge jumps in reserve balances say little about whether money is easy or expansionary — see an earlier post on the Great Depression for an example about this. Large scale asset purchases similarly do not indicate that money is easy or expansionary. I’ll have an upcoming post discuss exactly how easy/expansionary/loose monetary policy has been (a sneak peak: it’s not as expansionary as one might think).

The Fed’s quantitative easing programs over the last decade, including the current one, are not the same as recklessly printing money, do not monetize the debt, and are not that inflationary in and of themselves.