Note: any and all opinions are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cleveland Fed, the FOMC, or any other person or entity within the Federal Reserve System. I am speaking exclusively for myself in this post (as well as in all other posts, comments, and other related materials). No content whatsoever should be seen to represent the views of the Federal Reserve System.

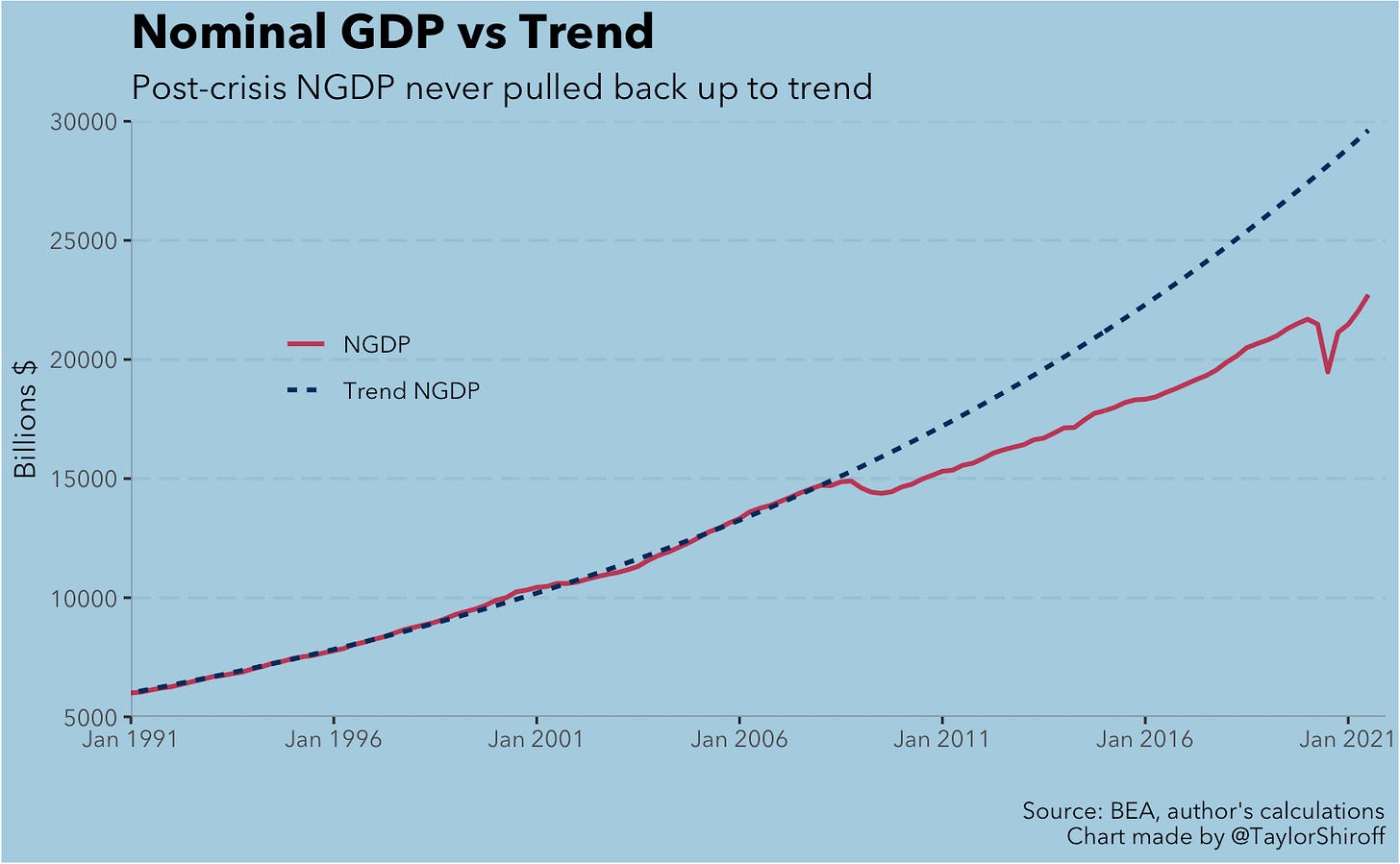

Today (July 29), the Bureau of Economic Analysis released their advance estimate of Q2 2021 GDP. It has confirmed we are experiencing a v-shape recession, finally ending over a year of debate. But it has also confirmed that are very unlikely to experience the same permanent drop below NGDP trend that we saw after the Great Recession. This is great news, and evidence that policy is working very nicely. But it’s not time to stop now.

Targets and the Fed

The Fed, of course, sees GDP as an indicator and not a target. The Fed has a Flexible Average Inflation Target (FAIT), and therefore targets 2% inflation on average in the long run, but we still have yet to hear or see what this actually means quantitatively. At yesterday’s (July 28) FOMC conference, I started to get a feeling that the Committee is more interested on averaging out medium- to long-term inflation expectations. Chair Powell seemed to indicate that though the belief that current inflation is mostly transitory is part of why the Fed is accepting of what he confirmed is higher than moderately-above-target inflation, another significant part is that inflation expectations over the long run are still anchored around 2%. This is somewhat in line with Milton Friedman’s 1990s conversion to targeting TIPS breakevens — inflation today doesn’t matter too much until expectations for inflation tomorrow are unanchored.

In any case, the Fed has an inflation target, and not a nominal GDP target. However, the Fed’s current framework has many similarities to an NGDP target. The path of the price level in a FAIT regime that makes up for shortfalls in unemployment and inflation should wind up looking something like the path of the price level in a price level targeting regime, a cousin on NGDP targeting. Consider the wording of the Fed’s Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy:

“In order to anchor longer-term inflation expectations at this level, the Committee seeks to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time, and therefore judges that, following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time. . . In setting monetary policy, the Committee seeks over time to mitigate shortfalls of employment from the Committee's assessment of its maximum level and deviations of inflation from its longer-run goal.”

This will ultimately stabilize the path of the price level, as it is essentially arguing for stabilizing the growth rate of the price level over time while also keeping it on its target path — keeping it in line with future expectations for where the price level should be.

Right Answer, Wrong Reasons

While this is not a nominal GDP target, it surely does look like one is in use right now. Nominal GDP is inching very close to its post-Great Recession trend line. This is excellent news for a few reasons, but perhaps most importantly it means that aggregate income is almost back on its predicted path. The point is that when income is below trend, we have less income to spend than we anticipated, and those anticipating receiving income from someone else’s spending wind up with less income — rinse and repeat. David Beckworth maintains an excellent (though not-yet-updated for Q2) measure of NGDP deviation from consensus forecasts, which essentially gets at the same idea.

This is a very different story from the last recession. Nominal income never returned to trend — and at this point, it never will. That anticipated future income never arrives and is pushed back to a much later date.

Policy this time around seems to on track to avoid this happening again, even though we do not have a nominal GDP target. Under a strict 2% inflation targeting regime, it is almost certain that policy mistakes would have been made. Thanks to what is essentially an alternate form of a price level target, nominal income seems set to avoid a sharp and permanent undershoot below trend.

On the real side, Jason Furman has pointed out that real GDP is now above its pre-pandemic level, while still below trend.

The two charts below, from Furman, show that real personal consumption expenditures and business fixed investment are still below their forecasted values from January 2020, but that they’re getting closer to where they were expected to be.

This is a tremendous policy success. The worst pandemic in one hundred years struck us 18 months ago, shutting down vast portions of our economy, shooting our unemployment rate up to higher levels than we saw during the Great Recession, and cutting major stock market indices by a third. And yet, policy has successfully resurrected aggregate demand to create an economic atmosphere strong enough that if an alien with no knowledge of the last 18 months decided to stop by today, they’d be unable to detect most of the pandemic’s impact.

Don’t Stop Now

As David Beckworth (we’re big fans over here) pointed out as a guest on his own podcast, another component of level targeting is to not just return to trend, but to make up for the lost income. He uses a driving analogy: if you leave your house at noon for an appointment 30 miles away at 1:00, you anticipate needing to drive at 60 miles per hour. However, if you run into traffic halfway there and sit still for 15 minutes, you’re going to need to drive faster than 60 miles per hour in order to get to that appointment on time. In other words, you have to make up for undershooting your speed target by overshooting it enough to feel like it never happened.

In the world of nominal GDP targeting, this translates to letting income rise above target enough so to match the amount of “missing” or “lost” income. Put another way, when nominal GDP falls below trend, it should subsequently run above trend so as the area between nominal GDP and trend is equal.

I show this graphically below. This chart essentially shows the cumulative surplus or shortfall in nominal GDP. When it is negative, it is negative by the amount by which nominal GDP would need to fall (in one quarter, which is unrealistic) to cancel out all the above-trend income. When it is positive, it is the amount by which nominal GDP would need to overshoot the trend in order to make up entirely for previous shortfalls.

For example, compared to the 2009-2020 trend, in January 2016 nominal GDP was running a bit over $1 trillion above trend. To “remove” that unanticipated excess income, nominal GDP would have needed to fall by that same amount, $1 trillion. This is a bit out of context, as I really should be comparing this to the pre-crisis trend, but let’s take a look at what would’ve been necessary for that:

Making up for missing income would’ve probably been a long shot by 2011 — by January 2016 this graph just looks like an exponential function.

Back to that previous chart: currently, about $7 trillion in extra, above-trend income is needed to cancel out the missing national income due to the pandemic. That’s quite a lot of money, but the good news is that the nominal GDP gap — the amount by which nominal GDP is above or below trend — is closing rapidly.

Remember, though, that closing the gap is not quite enough — ideally, we should make up for all that area below the x axis. That area represents that amount of “missing” income and spending — income and spending that had been anticipated and consistent with trend, but did not ultimately occur.

Fortunately, we seem on track to overshoot a gap of zero. We are very lucky that policymakers did not repeat the same mistakes of the Great Recession, which broke us off from sixty years of trend.

File > Save As > how_to_fight_recessions.png

Hopefully policy makers reflect on the successes of nominal income support during the pandemic. Through both increased government spending on unemployment and small business assistance as well as accommodative monetary policy that has been unafraid of above-target inflation, the mistakes of the Great Recession have been largely been avoided. When the next time comes — and there will always be a next time — I hope that policymakers remember the successes of these policies. I don’t know how much hope I have, though.

For now, though, it’s not time to take the foot off the gas. There’s lost income left to be recovered. Above-target inflation will assist in this, which is one reason why I won’t necessarily be upset when inflation for 2021 ends around 4%, as it seems likely to. For now, let labor markets tighten more (speaking of shortfalls, there is one in the millions in employment) and let the economy heat up a little more. We can begin to have a conversation about when to begin tapering asset purchases, but the time for that to begin is still around at least six months away. Rate hikes are even further.

But if the Fed does as it says, they should be on track to do the right thing. We just have to wait and see.