Note: any and all opinions are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cleveland Fed, the FOMC, or any other person or entity within the Federal Reserve System. I am speaking exclusively for myself in this post (as well as in all other posts, comments, and other related materials). No content whatsoever should be seen to represent the views of the Federal Reserve System.

Today the BLS reported that the CPI rose 0.6% in May and is up 5% from last year. “Oh no! Anyway:”

I am dismissive of recent higher inflation for two reasons: base effects and transitory effects, the same two given by the Fed for their nonchalance.

Base Effects

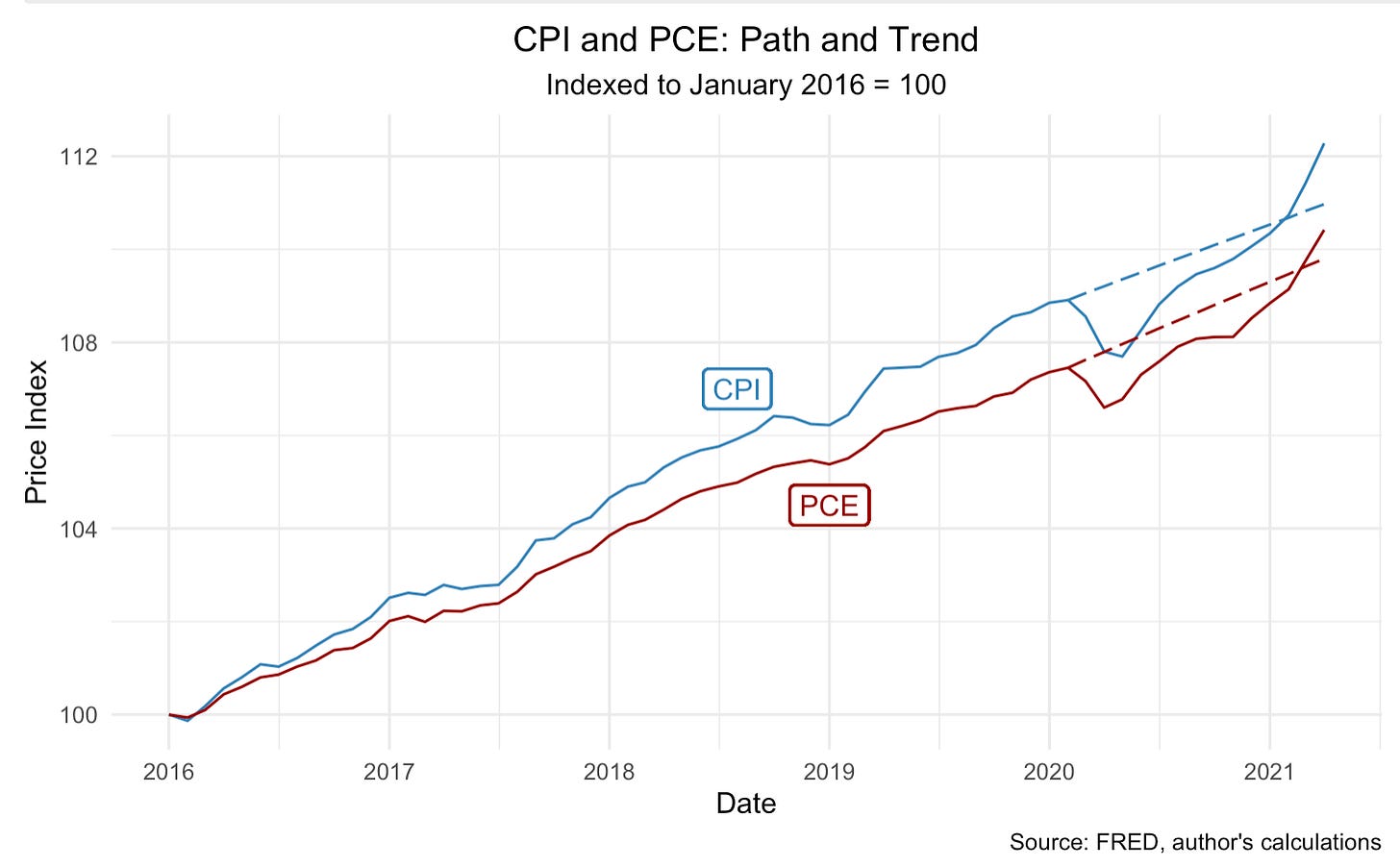

We can see base effects in the deviance of the CPI (I also show the PCE index, as it is the Fed’s index of choice) from the pre-pandemic trend Jan 2016-Feb 2020, the dotted line. Current data calls back to very low CPI/PCE readings that fell decently below trend:

While we are currently above the dotted line, recall that the Federal Reserve had great difficulty getting inflation to hit the 2% target, so some overshooting helps to make up for where we should have been, while also bumping inflation expectations up and closer to 2%. In any case, if we reference the inflation rate back to the trend line and not to what actually occurred, we wind up with a bit over a 2% inflation rate in either index.

This shows the utility of looking at the index itself, and not the inflation rate. The inflation rate is generally cited in year-over-year terms, but if one year ago (May 2020) had an index value at nearly May 2019’s level, a higher inflation rate should be in order to make up for this to keep the trend intact.

Transitory Effects

Transitory effects are impossible to detect from the raw inflation rate, but we can use other measures to impute the portion of the rate that is due to transitory effects. For this purpose, I am particularly fond of the Dallas Fed’s trimmed-mean core PCE rate (henceforth: TPCE).

TPCE takes the logic of core inflation rates and expands it beyond food and energy prices. Core inflation is a useful measure because food and energy prices are generally more volatile than other components of a price index. The issue with core price indices, however, is that many other components are just as volatile — if not more! See this chart from the Dallas Fed:

Many components in the core PCE index are just as or more volatile than food and energy prices. From month to month, this can vary from watches to telecommunications to used cars. TPCE cuts out or trims roughly the top and bottom quartiles of the highest and lowest price movers, and then takes a weighted average of what’s left. The chart below shows that “real” or “ultra-core” inflation was not as high as the FOMC felt it was in 2007-2008 (which was then the justification for not cutting rates even when economic activity slowed down), and that the Fed was hitting 2% very nicely from mid 2018 until the pandemic began.

We can interpret the spread between the raw PCE and the TPCE as the transitory component of inflation. Of course, this is the PCE index and not the CPI, and it does not account for base effects, but the spread is still a useful metric to determine the nature of inflation, transitory or permanent. When this difference is positive, reality is less inflationary than the general price level index suggests; when it is negative, reality is more inflationary.

PCE inflation in April was 3.58%, but the positive spread shows that roughly 180 basis points of the inflation rate might be considered transitory. Transitory inflation happens all the time, and in fact it is frequent and transitory enough that perhaps we should not really call it inflation but more of a price fluctuation. At the very least, we should be clear and explicit in referring to it as transitory inflation.

Not Everything Is Inflation

For those who claim that inflation is higher than reported and that it will continue in that direction, common anecdotes are not replacements for inflation measures. No, rising bike prices do not hint at “inflation peril looming for the U.S. economy”; rising rental car rates are not a good signal either; nope, not used cars either. Even Economics Explained, a YouTube channel with a million subscribers and 90 million views, argues that hyperinflation is “already here”.

I am publishing this before markets close for the day, so who knows how today will end. But for almost every daily push notification at the stock market’s close citing “inflation anxiety” for the day’s 1% decline, there’s a recovery over the next few days that continues to push the trend up. Did they forget about inflation? Did the situation really change so much in 24 hours? Is inflation being built into higher expected P:E ratios and suggesting stocks are actually undervalued?

Who knows! The market isn’t one person, anyway. Someone out there might have an unfulfilled buy order for a 10-year TIPS with a 5% breakeven. We do not make assumptions on him or her alone, but from what the TIPS market says. And they say about 2.4% at the moment!

Macroeconomics is about the aggregate, not the individual. We cannot make good assumptions off of activity in one market. Bikes, rental cars, used cars, iron, lumber, everything has had its moment as a prelude to hyperinflation. That requires basing the dynamics of the entire United States economy on the activity in a single market. And when supply and demand run their course in those markets and prices eventually fall, nobody claims that’s a sign of deflation.

What Really Matters

In any event, it is expectations that matter. Wage growth is really awesome, but not necessarily inflationary if matched with productivity growth. Market forecasts of inflation (TIPS) have been declining slightly, showing about a 2.5% average. As Janet Yellen said, this would be a good thing, as higher nominal interest rates would help restore policy options that are unavailable at the zero lower bound (assuming, as I unfortunately do, that many “unconventional” monetary policy options are off the table). This is why the return to the price level trend is a good thing, though I prefer a nominal GDP target over a price level target. At least moderate, ~2% inflation expectations are being made, and they will almost certainly be met in the medium- to long-term.

Inflation will become a problem when one is shocked by the prices upon entering a grocery store. Not the prices of just meat or coffee, but of everything in there, as if the store was having an inverse sale. This inverse sale cannot be expected to end, though; if you expect price increases to be temporary (perhaps a meat processing plant has been hacked, or a gas pipeline), your subconscious long-run expectations will be the same as before.

Imagine the following scenario: three years ago, you became a recluse and beginning in May 2018 you never left the house, not even for grocery shopping. In May 2019, you finally run out of supplies and head to the store, where you notice prices are about 1.8% higher than when you last were there. You wanted to go in May 2020, but the pandemic left the store shut down. Finally, in May 2021 you’re able to go again, and you find that prices were about 5% higher than the last time you went in 2019.

This would not seem odd or special or any different to you. 2% annual inflation during two years is a total increase of a little over 4%. 5% over two years is about 2.5% annually each year, so maybe inflation was a little hotter than normal, but surely nothing to freak out about. That’s the point of remembering base effects — it’s the deviation from the pre-existing trend that matters. If you think that some of the prices are higher than expected due to transitory factors such as a labor shortage or supply bottlenecks, then your underlying expectations for the future will probably remain close to trend.

The lesson here is that we need not freak out yet. The price level is running close to trend and just slightly above, creating healthily higher future expectations, and a substantial portion of the inflation rate is transitory and not permanent. If an alien came to check the price level every year but forgot to come check it last year, they would not be too surprised with the data they’re collecting now.

Fine, Some Reflection on 5%

Monthly inflation decelerated to 0.6%, down from 0.8% from March to April. Core inflation is at 3.8% year-over-year. 58% of the year-over-year increase in the main CPI can be accredited to transportation, which is up 20% from a year ago. Inflation without food, energy, shelter, or used cars was 3.5%.

Further information on the Dallas Fed’s trimmed mean PCE index is available here.