The Federal Reserve and Inequality

It's not their job, and the solutions offered would make it worse

Note: any and all opinions are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cleveland Fed, the FOMC, or any other person or entity within the Federal Reserve System. I am speaking exclusively for myself in this post (as well as in all other posts, comments, and other related materials). No content whatsoever should be seen to represent the views of the Federal Reserve System.

Much has been made of the Fed’s perceived role in worsening inequality since the beginning of the pandemic, from accusing it of “giving the stock market $1.5 trillion” to implementing low interest rates that generate “even wider wealth inequalities as the gap between the rich and everyone else grows”. The whole of Econ Twitter has been relentlessly (though correctly) criticising the linked New York Times piece (for an excellent and deeper commentary, see Joey’s great post), but I wanted to throw a couple quick thoughts out there. In this post, I will discuss the impact of Fed policy on inequality and why criticism that the Fed is worsening inequality doesn’t really make any sense.

Fed Policy and Inequality

Inequality and Fed policy have a long history. It last reached its peak in the response to the financial crisis. The Crisis Trifecta of Ben Bernanke, Tim Geithner, and Hank Paulson have often repeated that they “bailed out Wall Street to save Main Street”, but this defense never resonated with many. The Fed is an easy target from both sides of the political spectrum with a long-established track record of accusations ranging from serving only elite interests to being controlled by big banks.

But what effect does Fed policy have on inequality? There are two main channels: asset prices and labor markets.

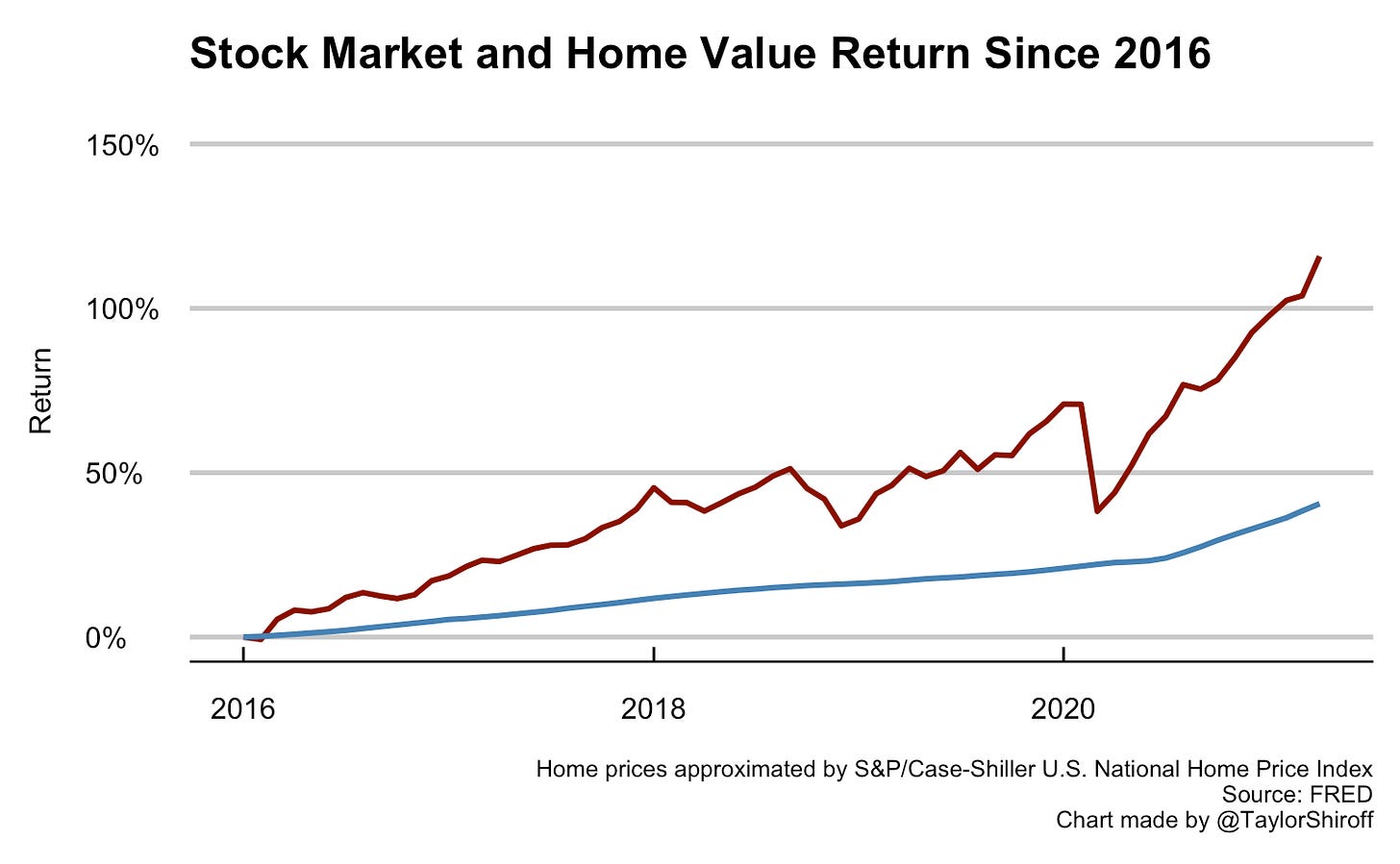

I hate the term “asset price inflation” for the same reason why I hate the term “used car price inflation”. Inflation is about an entire macroeconomic basket of goods, not microeconomic-level market behavior. But “asset price inflation” represents a very real dynamic: when the Fed cuts interest rates, fixed-income financial assets go up in price. For example, interest rates move inversely with bond prices. So if the Fed cuts interest rates, bond yields in general will fall too, which is the effect of their price having gone up. This occurs broadly with asset prices across the board, with home prices included. Quantitative easing has a similar, though possibly less direct, impact on the stock market.

The argument goes that this essentially only makes the holders of these assets better off. Quantitative easing is good news for you only if you own a home and/or hold an investment portfolio: something a third and about half of America doesn’t do, respectively. Therefore, some claim, the Fed worsens wealth inequality.

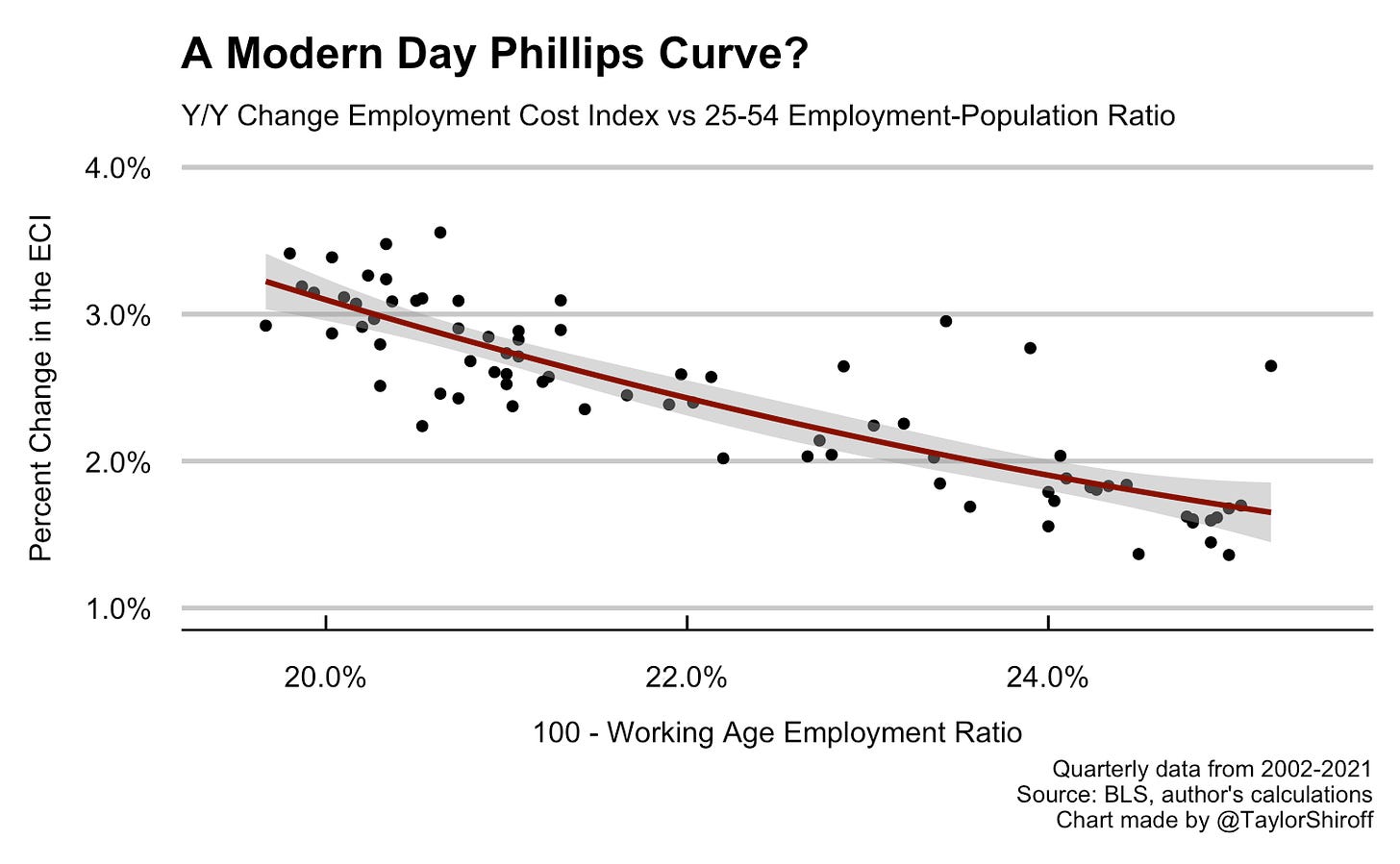

This is a bad argument. On the other hand, the Fed can sponsor tight labor markets, which are half of its dual mandate. Tighter labor markets should create real wage growth, which should benefit everybody across the board and cut income inequality. More employment is great, and the Fed has the tools to promote this — and they’ve been using them.

Tight Labor Markets Are Good, Actually

The issue is that in the short run, or even the medium run (whatever that might mean), the Fed cannot do that much to resolve wealth inequality without destroying the economy.

Consider the counterfactual that opponents of wealth inequality-creating Fed policy implicitly suggest would be better. No quantitative easing, and be in a mad dash to raise interest rates as soon as possible. Essentially, cause a recession to fight wealth inequality. I mean, what could be better for the economically vulnerable than causing a recession to prevent the wealth of the top 1% getting too high? (Arbitrarily high, I might add.)

What should matter is the ultimate outcome. We really do live in an instant-gratification society. It took labor markets a long time after the Great Recession to recover, and even then interest rates were raised too early (no matter for what reason, they were all probably bad ones). If a little bit of wealth inequality has to be created to boost long-term employment prospects and labor market tightness, that is a trade-off I am very willing to make. Getting people back into work is good for them and everybody else.

Is This Even Real?

Further, there’s reason to believe that monetary policy isn’t really worsening wealth inequality that much in the process of easing income inequality anyway. Across the ocean, Lenza and Slacalek (2018) found that European monetary policy during and after the Great Recession, which included quantitative easing, did not meaningfully increase wealth inequality while actually reducing income inequality:

“QE compresses the income distribution since many households with lower incomes become employed. In contrast, monetary policy has only negligible effects on the Gini coefficient for wealth: while high-wealth households benefit from higher stock prices, middle-wealth households benefit from higher house prices.”

A similar story surely applies to the U.S. too. Everybody across the wealth spectrum has something to gain. In fact, “asset price inflation” may be a good thing, so long as it isn’t literally just a bubble. Before his career at the Fed, Ben Bernanke (and others) developed the concept of the financial accelerator: rising asset prices boost the value of possible collateral to be used by firms to promote the flow of credit through the economy. When interest rates reach their effective lower bound, this can be a powerful mechanism to still further boost investment.

I think Chair Powell was entirely correct in his response to this criticism at his recent House testimony:

Who is seriously asking for higher interest rates right now? Even the inflationistas seem more in favor of controlling fiscal spending than raising interest rates.

The Fed’s focus on inequality is set correctly. Their view seems to be that inequality is best fought through tight labor markets and pushing the economy as close toward potential as possible. Fed communication seems mindful of the errors made during Yellen’s tenure as chair, partially thanks to last year’s framework revision. The Fed seems correctly set to not take their foot off the accelerator not just until substantial progress is made, but until that progress is forecasted to continue.

There’s Always a Trade-off,

but that doesn’t mean the correct action is inaction. If low interest rates create inequality, so be it. The good news is that they don’t seem to really do that, and that whatever inequality is generated by central bank action is justified by obligation to restore tight labor markets. That obligation is not arbitrary, but chosen because full employment is a really good thing for everybody. We’ve got a long way to go; there’s no time for a recession to fight inequality. What could be more regressive!