Tightening is more than tapering

The tightening cycle is well underway, even as rates are yet unchanged

Note: any and all opinions are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cleveland Fed, the FOMC, or any other person or entity within the Federal Reserve System. I am speaking exclusively for myself in this post (as well as in all other posts, comments, and other related materials). No content whatsoever should be seen to represent the views of the Federal Reserve System.

Monetary policy often reminds me of one of my favorite lyrics from one of my favorite Philly bands: “What new mystery is this?” (for real though, check these guys out before it’s too late; they’re currently on their second-to-last tour, ever).

The Fed has kept interest rates at zero for about the last 20 months. However, in this post I’m going to tell you that policy has tightened and is probably continuing to tighten as you’re reading this. At first, you might figure that I’m talking about the Fed tapering its asset purchases. It’s true: the Fed is slowing down its asset purchases, and they seem set to speed up the taper next week. But the purchases themselves don’t necessarily do that much, other than lower liquidity premiums. The real power is in what those purchases indicate.

In fact, the Fed is already well into the tightening cycle, tapering aside. Expectations of future short-term rates have risen, which means markets expect a faster timeline for the Fed to raise interest rates. This has bled into foreign exchange markets, where the dollar has strengthened considerably over the last few months. Commodity prices are slowing, with some even falling. Normally I’d point to declines in breakeven inflation rates too, but given our present circumstances I’ll set those aside for now. However, they do confirm that markets see the Fed as credibly committed to keeping inflation low.

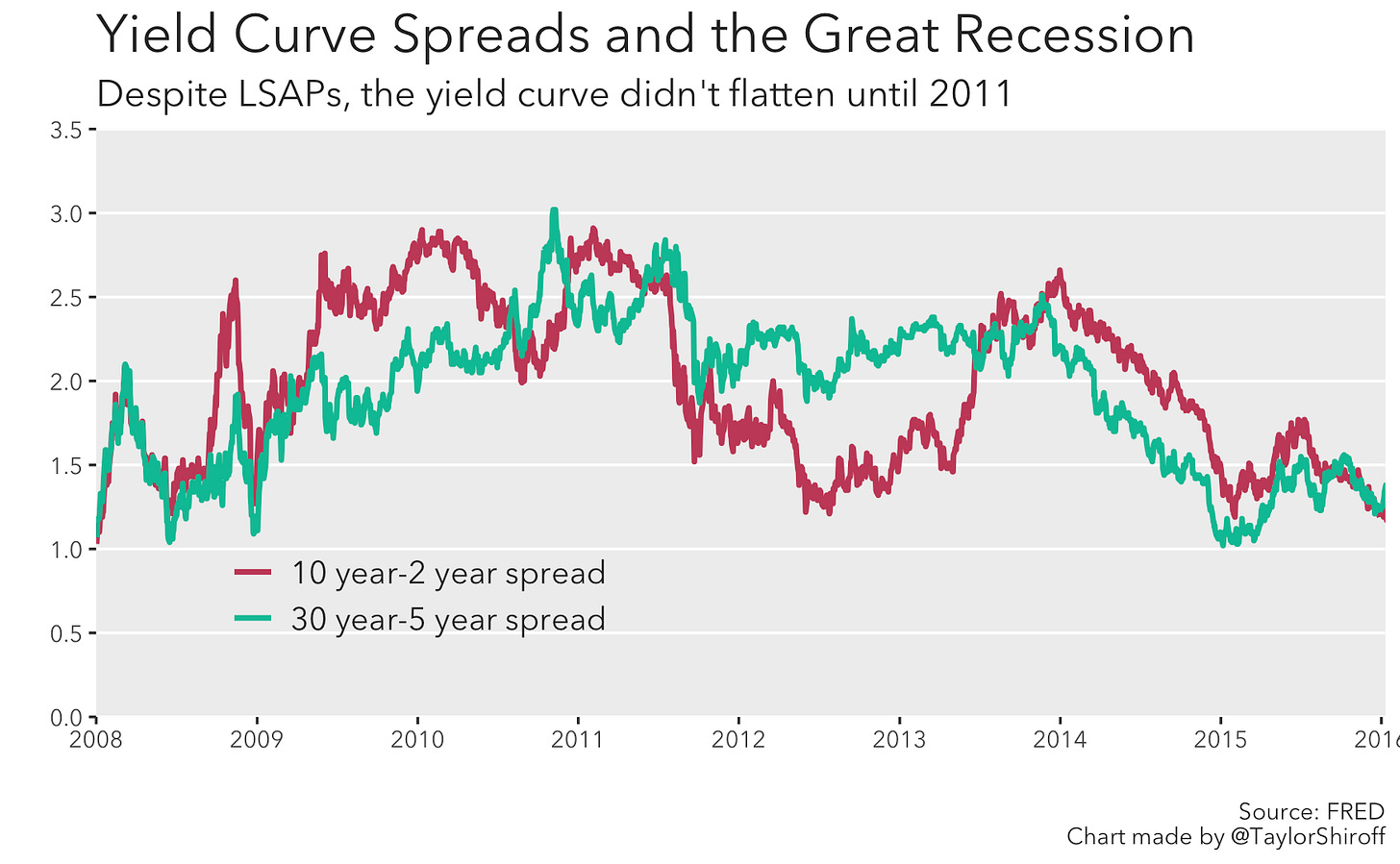

In any case, the signs are clear: the tightening cycle is here. Let’s start by looking at the yield curve:

The yield curve is a policy choice

Everyone who knows about the Fed knows that they control the shortest short-term interest rates in town. The Fed sets bounds for short term (generally overnight) repo rates and the near-obsolete federal funds rate through an array of policy tools. Through the reverse and standing repo facilities, the Fed has a firm (though occasionally imperfect) grip over where short term interest rates hang out; with reverse RP and IOR, the Fed binds the fed funds rate. For a few reasons that I won’t get too into here, the short end of the Treasury yield curve generally hangs around the fed funds rate:

Now here’s the fun part that people often miss: the yield curve is a policy choice, whether it’s consciously set or not. As Joey Politano argued in a great piece (from which I borrowed this section header; read it if you want some more background on the yield curve), the Fed could control exact yields throughout the entirety of the yield curve if it wanted to; it just has to be credible.

But even when the Fed isn’t trying to corner longer term interest rates the way it does with overnight rates, it still has enormous influence over the shape of the yield curve through setting expectations for the future path of short term rates.

Here’s how. Imagine you are choosing between investing in a two year Treasury note, or buying a one year Treasury bill today and then buying another one in a year. What price (or yield) would make sense for the 2 year note? It should probably be equivalent to buying a one year bill today and another in 365 days, since we could do that if we didn’t like the price (or yield) of the 2 year note, plus a little bit of term and risk premium to compensate for the wait and the stress. But alas, while we know what a 1 year bill yields today, we don’t know what the 1 year note that we’ll buy in 365 days will yield.

But wait—the 1 year bill tends to trade close to the Fed’s target range, plus rate hike expectations over the next year. If the Fed has given us enough clues about where it’ll have its target rates in one year and how it will respond to future data, then maybe we can use that to guess what the 1 year bill will trade at next year. So the 2 year yield, then, should be a product of today’s 1 year yield and the 1 year yield we expect to see in 365 days (with some term and risk premium sprinkled in). This logic works through the rest of the yield curve, too: so much of it is based on the expected path of policy.

But who else other than the Fed controls expectations of the future path of short term interest rates? After all, the Fed does two kinds of OMOs: open market operations, and open mouth operations. The Fed controls the expected future path of policy either explicitly (i.e., by committing to hold rates at zero until the economy has reached a certain point) or implicitly (i.e., by choosing a tapering speed to set the end date of asset purchases). The Fed’s metric for taking interest rates off of the zero lower bound—maximum employment and sustained inflation at 2%—is an example of an explicit projection of the path of future policy.

The timeline of asset purchases is an important implicit projection of future policy. Time and time again, the Fed has clarified that it will not raise interest rates while still purchasing assets. To them, this constitutes pressing the gas and the break at the same time. Whether that’s true or not, one thing is for sure—markets take the Fed for their word and expect them to stop purchasing assets before they raise interest rates. In a way, asset purchases are as good as a guarantee that interest rates will remain at zero for as long as they are ongoing. This is why all the talk about the Fed speeding up the tapering process has already had effects on financial markets without the Fed having even done it yet.

Making markets believe

Whether you think the literal purchase of assets is monetary accommodation or not (the portfolio balance channel is real, but in my opinion, the effect is probably overstated), one interesting factoid about quantitative easing and asset purchases is that they didn’t really seem to work until the one year forward rate came down. If the point of quantitative easing was to lower long term yields (and thus flatten the yield curve), it didn’t seem to work until mid 2011.

How could this be? The Fed purchased $600 billion in Treasuries between November 2010 and June 2011; were they just not buying enough? Well, at the August 2011 FOMC meeting, the first meeting after they concluded that round of asset purchases, a new line was slipped into the FOMC statement:

The Committee currently anticipates that economic conditions--including low rates of resource utilization and a subdued outlook for inflation over the medium run--are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through mid-2013.

Remarkable! For the previous two years, the Fed had been sticking to saying that they expected “exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate for an extended period” in each FOMC statement. Note: exceptionally low, but not necessarily zero. Note: for an extended period, but you can decide what that means. Sure, there was a lot of bad economic data coming in at the time. But that wasn’t necessarily that new. Yeah, equity markets crashed in the week earlier for a number of reasons, but while bonds did act as a destination for a flight to safety, the yield curve flattened faster, further, and for longer than earlier in the crisis. And the yield curve did not flatten, nor did the one year forward rate stay as low as it did, for as long as they did until the FOMC changed their wording.

In early 2012, the liftoff forecast was adjusted to late 2014, then later to “at least mid-2015”, before being ditched for the Evans Rule at the end of the year. The Evans rule switched to a quantitative measure for justifying lifting off of the zero lower bound: 6.5% unemployment, unless inflation rose above 2.5%. The one year forward began to rise in late spring 2013; almost exactly a year later, in April 2014, unemployment finally fell below 6.5%. Remember that the one year forward rate is roughly the expected one year Treasury rate in one year. That rate in one year also includes expectations for developments in that same year. In other words, the one year forward in spring 2013 included expectations for the period spring 2014-spring 2015. So markets were a little bit early, but their reading lined up with what the Fed did pretty well.

Now, I’ve been talking about the front end of the yield curve for a while. But what else is the back end of the yield curve but ten or thirty years of investing at the front end, with a little bit of risk and term premium! (Dear financial economists: please excuse my continuing oversimplification. Obviously there’s more than that, but my point still stands.) Quantitative easing only “worked” once the Fed convinced markets it really wouldn’t raise rates in the short term.

Now, it’s implicitly understood that the Fed would not raise rates until it has finished tapering its asset purchases; in fact, that’s why many Fed officials are calling to move the tapering timeline forward, so that rates can be raised sooner. Markets are receiving this signal loud and clear:

Tightening is more than just tapering

And that’s why tightening is more than just tapering asset purchases. Over the last month or two, the Fed has made a communications turnaround: all of a sudden, it seems to be getting quite concerned about the duration of inflation and it seems quite satisfied with employment progress. Talk of moving the tapering timeline forward went from being a sideline view to one supported by Chair Powell himself. All this talk is already having effects, even before the Fed has had the chance to review the speed of its taper process (which it is set to do next week).

For a while now, the consensus has been on a first rate hike at the Fed’s June 2022 meeting. That consensus was so ingrained in markets that one year forwards rose after June 15th—the exact date of next year’s meeting—earlier this year. But since September’s FOMC meeting, the one year forward has risen further, which suggests that markets expect more than just one or even two rate hikes over the next year. In fact, over in the federal funds rate futures market, traders seem to expect three rate hikes by the end of 2022.

The Fed funds market assigns a considerably-nonzero probability to four rate hikes by the end of the year, too:

This is a big deal because of how much stuff is priced off of Treasuries—corporate borrowing, in particular, but also mortgages, among other things. When higher interest rate expectations affect the yield curve, they affect the cost at which corporations can borrow—even if the Fed hasn’t done anything yet!

What’s interesting about this stage of the tightening cycle is that the ten year yield has not budged up too much; most of the shifts in the yield curve have been on the short end. While the ten year yield, for example, is above its summer lows, it’s still down almost 20 basis points from late October. One reason for this is that markets might expect the Fed to go too far, too fast. The Fed’s rate-hiking strategy tends to be to hike until something breaks; it seems markets are expecting short term rates to peak and fall not too long after.

Tightening is more than just bonds

The tightening cycle is well underway in other asset markets, too. The dollar, for example, has strengthened quite a bit over the last month or two. Higher interest rates are generally associated with a stronger dollar, and vice versa for lower interest rates (see: interest rate parity). Check out Bloomberg’s dollar index:

A stronger dollar means American exporters will be sending pricey goods to foreign markets, and that foreign goods will be cheaper for Americans to buy than domestic goods. A stronger dollar might also mean that markets are expecting the Fed to tighten further relative to other central banks, which provides another angle on the expected future path of short term interest rates. If both of these cases play out, that will mean American businesses will face weaker aggregate demand, which could possibly ease inflationary pressure.

Commodities are feeling the pull down, too. Natural gas and oil prices both began downward trends last month. Gold, silver, and copper prices are stagnating, and even agricultural commodities—cattle, wheat, corn—are beginning to slow, flatline, or head down. Time will tell if these are temporary declines possibly related to Omicron or a true shift in trend, but the effect of hawkish open mouth operations is still clear: prices, especially in futures markets, are coming down. This is a reflection of the fact that markets expect the Fed to take price stability seriously; they won’t let prices continue to rise too much, too fast.

Eurodollar futures also offer a fascinating insight into how rate hike expectations have evolved. The eurodollar futures contract expiring in June 2022 went from implying a 0-0.25 fed funds target range (the current situation) up until early October, but is now implying at least one and possibly two rate hikes by June 2022 (the 0.25 to 0.5, or 0.5 to 0.75, range). The June 2023 contract is even wilder: after spending March through October expecting two rate hikes by June 2023, its price now implies an expectation of five rate hikes by June 2023. Markets also expect the Fed to finish their hikes at the 1.50-1.75 or 1.75-2.00 range, a level well below the Fed’s own expectations, and for them to reach that point by December 2023. That would imply a rate hikes at about every other FOMC meeting between June 2022 and the end of 2023.

The stance of monetary policy

Hopefully by now we’ve all learned that the Fed’s target interest rate is not a good indicator of the stance of monetary policy. I know a certain sect of macroeconomics that loves NGDP as an indicator, but due to its infrequency I’ve kept that out of the discussion for now. The yield curve, exchange rate, and interest rate futures provide high frequency updates on the stance of monetary policy, and their story is clear: it’s tightening.

Now, this makes the Fed’s 2022 moves a little tricky. If they raise interest rates as fast as the market now seems to be expecting them to, it’s not hard to imagine the yield curve inverting next year, which would certainly not be a good economic indicator. But the question is whether the future is locked in. Will the Fed actually raise rates two, three, or even four times next year? Does the Fed have free will? Do you?

There’s nothing forcing the Fed to raise rates. Its forward guidance was simply sustained inflation at 2% and maximum employment. Obviously we can check off the first half (though there are legitimate arguments over whether it will truly be sustained or not), but the Fed has yet to coherently define maximum employment. If the Fed hops on the “85% prime age EPOP or bust”-train, perhaps the Fed need not raise rates for years! But markets are undoubtedly forecasting the Fed to raise rates quickly and strongly next year. And of course, markets have been wrong before:

But it’s not about whether markets were right or wrong—it’s about what they did in light of the information they had at the time. If markets genuinely expect short term rates to rise over the near term, then they’ll price assets accordingly. That means higher borrowing costs, shifted future investment plans, and a stronger dollar.

The Maradona Effect

Since all of these things are capable of slowing aggregate demand, so long as markets genuinely believe the Fed will tighten policy, they’ll do the work for them. That is, it’s almost as if markets are raising rates for the Fed. t+1’s short term rates have already been raised by the market; the only thing left to do is to raise rates in period t. This has the possibility of bringing aggregate demand and inflation down without the Fed even doing anything. If this occurs on schedule, perhaps the Fed won’t actually have to raise rates as many times as the market is expecting it to next year.

This is an example of what Mervyn King called the Maradona Effect:

[Diego] Maradona ran 60 yards from inside his own half beating five players before placing the ball in the English goal. The truly remarkable thing, however, is that, Maradona ran virtually in a straight line. How can you beat five players by running in a straight line? The answer is that the English defenders reacted to what they expected Maradona to do. Because they expected Maradona to move either left or right, he was able to go straight on.

And the analogy to monetary policy:

Monetary policy works in a similar way. Market interest rates react to what the central bank is expected to do. In recent years the Bank of England and other central banks have experienced periods in which they have been able to influence the path of the economy without making large moves in official interest rates. They headed in a straight line for their goals. How was that possible? Because financial markets did not expect interest rates to remain constant. They expected that rates would move either up or down. Those expectations were sufficient – at times – to stabilise private spending while official interest rates in fact moved very little.

The Fed absolutely has taken a hawkish turn in its tone and therefore forward guidance. In the last two or three weeks, it seems that a majority of the FOMC has turned in favor of speeding up the tapering process. Many, including Chair Powell, have changed the way they talk about inflation—no more “transitory”. If the Fed convinces markets enough that it’ll follow through on their word, markets might just believe them and act like the Fed already has.

The Fed has already raised next year’s interest rates, strengthened today’s dollar, and helped pull down commodity prices. While there isn’t much time to spare (if the taper is sped up, it’ll likely conclude in March, just 4 months away), the Fed might just be doing enough to bring inflation and “excessive” aggregate demand (in terms of its origins in the private sector, at least) down just enough so that maybe, just maybe, it won’t have to raise rates as quickly and as high as both it and markets currently believe it will. And besides, inflation is likely to fall relatively rapidly around the middle/second half of next year, which would give the Fed some space to hold off on rate hikes.