Why We Shouldn't Doom Over Labor Force Participation

Today’s Low and Stationary Labor Force Participation Rate Is Not a Sign of a Structural Shift

Note: any and all opinions are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cleveland Fed, the FOMC, or any other person or entity within the Federal Reserve System. I am speaking exclusively for myself in this post (as well as in all other posts, comments, and other related materials). No content whatsoever should be seen to represent the views of the Federal Reserve System.

Note: Joey Politano kindly let me write this post as the first guest post over on his outstanding Substack, Apricitas. I’m reposting it here for those who haven’t seen it. If you’re not subscribed to Joey’s blog, absolutely click this link and fix that!

If you’re reading about macro hot topics and it’s not about inflation, the supply chain, or fiscal policy, odds are that it’s about the labor market. Though the American economy has been able to put 21 million workers back into work since the trough of the pandemic’s economic footprint, there are still 4.2 million fewer employed workers than just 20 months ago.

There has been some concern that we might be left with a permanently smaller labor force, perhaps through a lower participation rate, or an increase in so-called structural unemployment. Some have put light on the “labor shortages” reported throughout our economy; others suggest that older workers might never return to work. Some point to how the labor force participation rate has hardly budged over the last year.

Thankfully, there are good reasons to be skeptical that these are permanent fixtures in the American labor market. I don’t buy that labor force participation is entirely meaningful at the moment; nor do I believe that a wave of retirements will hold the economy back. Instead, it seems that older folks and parents need the pandemic to subside further before they are able to return to work, and that there’s no good reason for “structural” unemployment in the long run to be any higher. Therefore, there is no reason for policymakers or observers alike to accept a smaller workforce as “full employment”. Jobs are good, and policy should let them keep coming along.

The BLS Makes Up the Numbers Anyway

Okay, maybe they don’t, but I think it’s useful to quickly revisit where these numbers come from. It’s really hard to tell who is and isn’t participating in the labor force. This chart from Employ America helps to show why:

It’s not even easy to tell who is unemployed and who isn’t! The BLS only counts you as unemployed if you are without a job but looked for work in the last four weeks. Looked for one five weeks ago, but had to worry about other things in the last four weeks? You’re not unemployed, but out of the labor force. That leaves only the employed and the actively-searching unemployed in the labor force.

For this reason, instead of the unemployment rate and labor force participation, it’s much more useful to think of labor outcomes in terms of “employed” and “not employed”. Plenty of people who are not participating would like to be participating, but need some condition to be met first (the right wage, job, employer, or even for the pandemic to fade away). In fact, while the CPS says that there were 7.4 million unemployed in October, it also counted an additional 6 million who were not in the labor force, but wanted a job now. Of those 6 million, 1.6 million looked for work over the last year and are willing to work now.

The number of those who haven’t looked for work over the last year but want a job, 4.4 million, contains roughly a million more people than it did from 2018-2019. It’s not hard to imagine parents without reliable childcare needing to stay home to care for their children. Without wading into the “did unemployment benefits disincentivize getting a job” discourse, one thing the enhanced unemployment benefits definitely did do is provide some of these households with at least a cushion of cash to help them get by without forcing the parent(s) to remain working. Immunocompromised workers or those who might live with immunocompromised or older family could also easily fall into this category—the risk of going to work and bringing something home is just too strong for working to be a rational move. However, these people aren’t counted as unemployed by the BLS—they’re out of the labor force. This is one reason why employment-population ratios are king.

Recall that we are down 4.2 million jobs since before the pandemic, which doesn’t even account for how many more workers we might’ve been able to get into jobs had there been no pandemic. At the same time though, there is no shortage of potential workers between the 7.4 million unemployed, 1.6 million who recently looked for work and are willing to work, and 4.4 million who haven’t looked for work but would like a job. Job searchers and employers just need the right contexts in order to find the right matches. That might involve a little more of waiting out the pandemic, letting the recovery finally spill over into services, and/or just letting time pass—more on that later.

Regardless, while the labor force participation rate has hardly budged since summer 2020, the employment-population ratio tells a somewhat different story. The labor force participation rate has hovered around 61.5% since June 2020; the employment-population ratio has risen from 54.6% to 58.8% over the same period.

This largely reflects a lower job finding rate for the unemployed. Each month since summer 2021, around 25% of the unemployed became employed; about 50% remained unemployed, and 25% left the labor force. By comparison, right before the pandemic in winter 2019-2020, 31% of the unemployed were entering employment, 45% were remaining unemployed, and 24% were leaving the labor force.

Most of the rest of this post will dive into some of the sources for why employment can fully recover, along with the labor force participation and employment-population rates. First up:

Retire the Retirement Argument

One argument that’s gotten a lot of attention recently suggests that many older workers simply retired during the pandemic and won’t be coming back, leading to lower labor force participation and overall employment levels. This is an argument that I have a hard time buying into.

Before turning to the data, it’s not as if older workers have no reason to temporarily step out of the labor force. While most older folks are vaccinated, it’s hard to argue that remaining concerned about a pandemic that hits the oldest the hardest is irrational. However, one way or another the pandemic will go away, either materially or mentally. Some may have picked up childcare duties that prevent employment, while others might be in the same boat as many who are out of the labor force and not considered unemployed: not out forever, just needing the right job, employer, and wage.

Turning to the data, we find that 9.6 million Americans 65 and older without disabilities were employed in February 2020; 9.3 million were employed in October. In fact, the employment level for these folks recovered similarly to those 25-54, with a slower recovery between last winter’s COVID wave and the mass distribution of vaccines.

It’s helpful to think about how much each age bracket is contributing to “missing” employment. Let’s consider February 2020 our baseline level; any employment below that level is “missing”, or, god forbid, a “shortage”. What this graph shows is each age group’s contribution to that shortage (note: values don’t always add up to 100 due to rounding).

At this point, the remaining shortfall in employment seems to be largely driven by declines in prime age female employment, not by retirees. So, even if older workers are retiring, their doing so cannot be a main explanatory variable for a “labor shortage”.

But are workers even retiring, like, for real? Similar to labor force participation, it’s hard to tell who is retired and who isn’t. Over on Twitter, Nick Bunker has this chart showing that the employment-to-retirement rate is more or less the same as before the pandemic. The only difference: the retirement-to-employment is still a bit lower than before (see this other tweet showing a recent rise in the unretirement rate).

In other words, American workers are retiring at normal rates, but American retirees are rejoining the labor force at lower rates. As Nick pointed out in another tweet (which he was unfairly ratioed for), this trend has started to reverse. While initially it might appear to be a bad thing that older workers need to return to work, it should be remembered that many of these workers were among those who were unemployed but eventually gave up on the job search. Remember how the unemployment rules work: if you didn’t look in the last 4 weeks, you're not unemployed but out of the labor force. Older workers left the labor force after giving up looking for work during the pandemic, which some figured represented a wave of retirements. Not so—it was more a rational (and largely involuntary) withdrawal from the labor force.

All this in mind, it seems unlikely that we’ll be faced with perpetually lower employment due to any sort of “structural” shift related to retirements. As with the next group up for discussion, many older workers simply just need the right conditions to be met before returning to work.

Parents and the Labor Force

Another group temporarily held back from employment is parents. The differential impact of the pandemic on men and women, and between married individuals and non-married individuals, is clear in the data. Married women lagged behind married men in returning to work until October of last year, but both married men and women have more or less had their recovery stall since then.

Note that this is not the case for single (unmarried, at least) men and women. In fact, more unmarried men are working now than were before the pandemic.

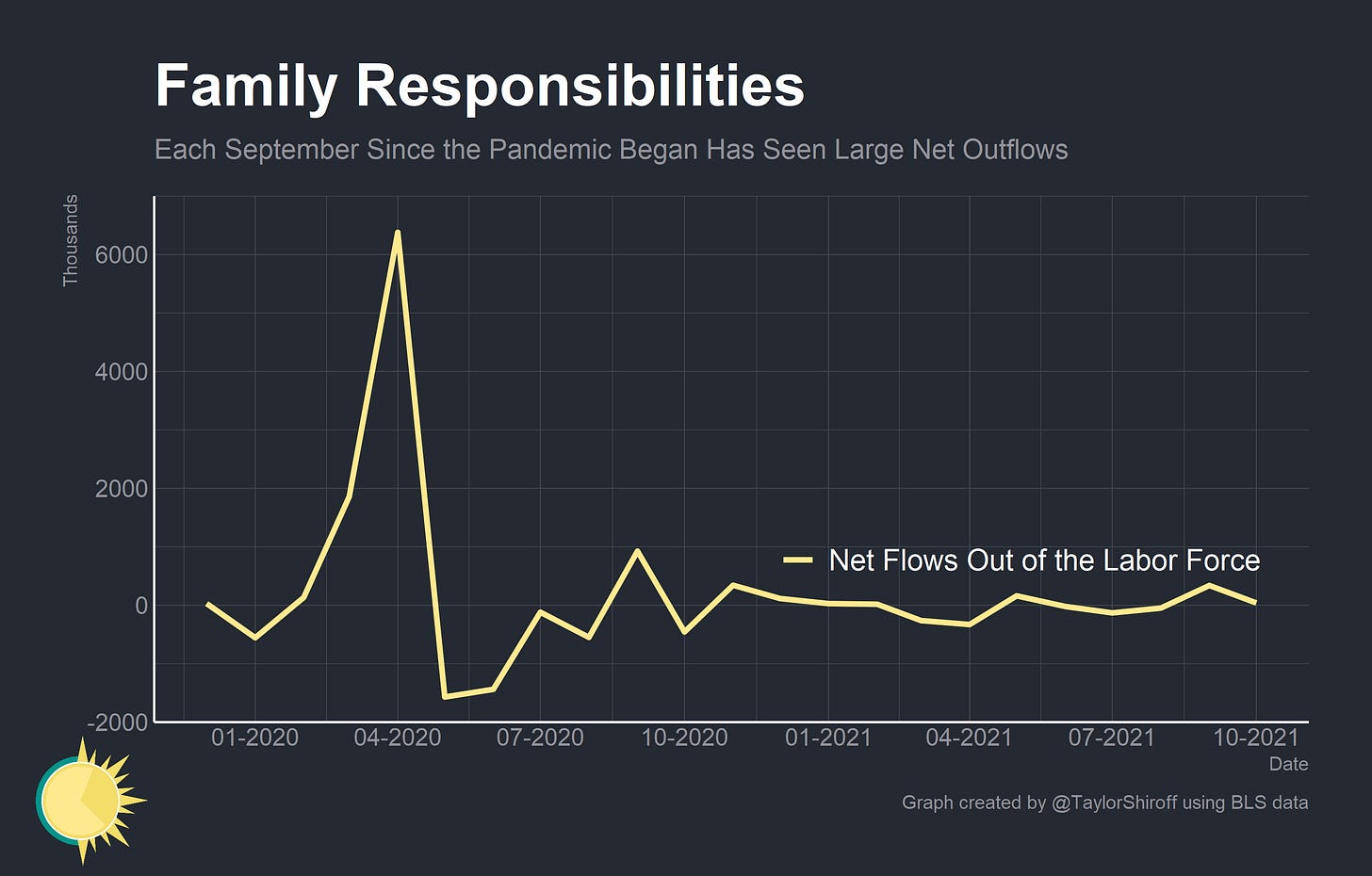

Childcare needs are likely to be the driving factor here. While most children are back in the classroom, that doesn’t stop a temporary switch back to online learning if a student or teacher becomes sick. We can see this when we look at net flows out of the labor force (as in, flows out of the labor force minus flows into the labor force). Of the 20 months now that we’ve been living with the pandemic, two of the five largest monthly net flows out of the labor force occurred in September 2020 and September 2021, marking the start of the school year.

As I discussed earlier, this effect is not equal between men and women. Women bear a disproportionate amount of child and family care responsibilities in American society. As a result, they left the labor force at much higher rates than men in September 2020 and especially in September 2021. The imprint of the delta variant, beginning in spring 2021, is clear.

The good news is that, again, this cannot be a permanent reality. I don’t want to jinx it, but barring an unfortunate surprise, next year’s school year, summer camps, and daycare should look pretty normal. Once again, it would be a mistake to look at stalling labor force participation and to accept it as a new normal—things can get better than this, and policy should aim for that.

A Track Record of Doom and Gloom

Labor force participation and employment doomers have a pretty bad track record anyway. During and after the Great Recession, many worried that many of the jobs lost would simply never come back—sound familiar? While it took longer than would’ve been ideal, employment recovered almost entirely in motor vehicle production, real estate, finance, and construction—the industries that were at the heart of the Great Recession and that were assumed to be forever scarred.

Labor force participation showed a similar rebound too, but you have to kind of look for it. As this FRED blog post explains in more detail, if you hold each age group’s share of the population constant, the labor force participation rate pretty much recovered entirely to its pre-recession level. This suggests that aging—particularly as the Baby Boomers retire—distorts labor force participation rates. For example, when one looks at the overall headline labor force participation rate, it appears to have flatlined around 2014. However, around the end of 2015, the labor force participation rate for prime age 25-54 year olds began a turnaround that would bring it back to pre-Great Recession levels.

Of course, if one had been looking at the prime age employment-population ratio, they would have seen a nearly linear jobs recovery begin in 2011. But the point remains the same—it’s not a great bet that jobs are just “lost forever” and that the unemployed will forever struggle to rejoin the labor force. To “bring jobs back”, impacted sectors need to see renewed and strong demand and to make relevant investments.

Full Employment is the Name of the Game

By my rough calculations, if we can continue recent strong employment gains, we’ll be very close to the pre-pandemic prime-age employment rate by around the end of next year/the start of 2023. If we’re able to keep it going even longer, we’ll be close to 2000’s peak sometime around the end of 2024. We’ll need consumer spending on services to recover and finally catch up to goods spending for employment in services to return to its pre-pandemic level. This will depend on the path of the pandemic, but recent data show a rapidly recovering demand in some sectors, as seen in food service (which, as a general category, is still down the most in terms of employment).

There’s no need for doomerism over labor force participation. To avoid using a cursed and forbidden word, many factors affecting participation in the labor market are temporary. Barring some unfortunate development, this coming summer should bring a return to summer camps and should be followed by a full return to classroom instruction with far fewer switches to online instruction. With the availability of booster shots and more widespread vaccination, older workers should feel more comfortable returning to the labor force. And regardless, the labor force participation rate is a dirty measure that is struggling to tell us much about the current state of the labor market.

We can still reach (and we should aim for!) the promised land of 85% prime age employment—nothing about the pandemic has made that impossible.