Recessions and rumors of recessions

The Fed is putting this strong recovery in peril

Note: any and all opinions are entirely my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cleveland Fed, the FOMC, or any other person or entity within the Federal Reserve System. I am speaking exclusively for myself in this post (as well as in all other posts, comments, and other related materials). No content whatsoever should be seen to represent the views of the Federal Reserve System.

Hey there, remember me? It’s been a little while since I’ve written here. If you’re among my many new subscribers, welcome! I appreciate your interest, and feel free to follow me on Twitter (@TaylorShiroff) for more.

I’ve been busy with a few other projects, among them self-recording an album (hopefully out soon!) and writing a book (definitely not out soon!). The book is a genealogy project that wound up becoming a truly fascinating story of Jewish immigration to the United States. I’m looking forward to sharing further details on it in the future—in the meantime, feel free to message me about it if you’re curious or interested. I’ve also moved to Cleveland to start my new job at the Fed (on Monday), which I am so very much looking forward to. I think it goes without saying that there could hardly be a more interesting time to be joining the Fed!

In this post, I will try to interpret the current US macroeconomic climate and offer my perspective/model of what is going on and where the near future may take us. In essence, recent policy decisions, Fed communication, and an unpredictable Fed reaction function pose significant risks to the state of the economy. There is a greatly-increased risk of a policy-prompted recession in the near future, intentionally or not.

Are we in a recession?

With an employment gain of 372,000, Friday’s jobs report confirmed that we are unlikely to be in a recession right now, even in the face of relatively dismal consumer expectations and a likely second consecutive quarter of negative GDP growth. Furthermore, weekly initial unemployment claims are about where they were in 2017, though they have risen somewhat. The more troubling aspect of this jobs report was the data from its household survey, which found that the prime age employment rate actually declined.

Instead of hinting that we are in a recession, this jobs report may provide hints that there is a recession to come. It’s not the data—again, it was an overall good report—but rather the Fed’s response to it. After the report’s release, the Atlanta Fed’s President Bostic suggested that the report validates another 75bp hike at this month’s meeting, and it’s likely that others follow his lead. After nearly two years of hoping for strong jobs reports, the Fed is likely concerned that June’s jobs report wasn’t soft enough.

Yet Americans have grown incredibly pessimistic about the economy, and their expectations for the future have soured, too. All of a sudden, we find ourselves talking about a recession and hearing about it seemingly everywhere: on TV, Instagram, on the street. Some (perhaps a large) part of the blame can go to increased political polarization, but this cannot to explain it all. High inflation is the main culprit: people simply do not like inflation. For many, inflation—and higher gas prices in particular—means tighter budgets and less consumption (in real terms). Their hard-earned incomes are no longer going as far as they used to.

Readers may be aware that I am generally skeptical of the idea that inflation expectations—particularly consumers expectations—have much of an effect on actual inflation (see this). But there is at least one important consequence of inflation expectations: they inform consumer expectations about the strength of the current economy as well as their expectations for its future trajectory. Inflation expectations and macroeconomic expectations often move inversely. Put simply, high inflation readings and expectations give off bad vibes about the economy, while lower ones radiate better vibes.

Though consumer inflation expectations remain relatively low—contrary to the Fed’s unfortunate knee-jerk reaction to preliminary Michigan survey data—they are above pre-pandemic levels.1 Contrary to earlier stages of the recovery, the uptick in inflation now comes from a wider base of goods and services. This ensures that rising prices appear frequently in everyday life, raising inflation expectations while also passing along negative sentiment and uncertainty about the state of the overall economy. Added uncertainty, especially over future income and employment, further dampens consumer spending, particularly on non-durables and services.

The Fed is doing its part

With high inflation, higher inflation expectations, and greater economic uncertainty likely to persist for some time, consumers may do much of the economic dampering on their own—a vibecession, per Kyla Scanlon. But in addition to weak consumer sentiment, the Fed seems all but set to deliver a recession at some point in the coming year—despite Chair Powell’s admission that though a Fed-caused recession is “certainly a possibility”, it would not be the Fed’s “desired outcome”.

It’s hard to square that with June’s SEP, in which the Fed drastically lowered its growth expectations for the near term, shifted its unemployment forecasts for 2023 and 2024 up, and suggested that it already expects to cut interest rates in 2024 (market are betting it’ll happen earlier). These figures suggest that the Fed expects nominal income growth to slow below “ideal” levels in the next few years. Maybe this all can happen without an explicit recession, but it would at the very least still look like a serious economic downturn. The best the Fed can do, officials insist, is to take things as they come: data release by data release, news piece by news piece.

But the Fed’s current “play it by ear” forward guidance style all but guarantees that they go too far. There is no known “stopping” or “slowing” indicator for future hikes, and the Fed seems set on using lagged indicators to determine policy. This only adds to the uncertainty. It may seem smart to wait for more inflation data comes out before committing to future decisions, but the only new data the FOMC will have when it meets at the end of the month will be last month’s data.

Many of the biggest contributors to high inflation readings also have little direct tie to Fed policy. How far will the Fed have to hike rates for the price of gasoline or natural gas to come down? If the global surge in energy prices proves to be long-lasting, inflation will remain high for some time until base effects kick in, which will take until around February or March of next year. Until that point, the annual inflation rate is likely to remain stubbornly high, unless the fall in commodity prices—which itself may be a warning of trouble ahead—is permanent. Will the Fed continue to hike rates anyway, until something breaks?

Recessions and rumors of recessions

2Considering weak consumer expectations, abundant uncertainty, and a trigger-happy Fed, it shouldn’t be a surprise that economic conditions are already slowing as financial conditions tighten. As the Fed raises interest rates, risk premiums and borrowing costs rise while asset prices fall; through tighter financial conditions, this eventually chips away at investment, slowing employment growth and ultimately nominal income growth. By lowering expectations for future nominal income growth and demand, the Fed discourages investment while simultaneously squeezing financial conditions even tighter. If policy is too tight, this may become a feedback loop.

This process seems already under way. Risk premiums do not appear to have risen much for equities, but medium-grade bonds and below have seen relatively large increases in their option-adjusted spreads. Spreads between corporate bonds and the ten year treasury yield are rising. The stock market (of which the Fed is only one input into pricing, of course) has technically fallen in bear market territory. The effectively unmoved equity risk premium implies that reflects higher risk-free rates more so than higher risk aversion, but the decline in equity prices still matters—and risk premiums can easily push them even lower if expectations and/or reality darken.

Real interest rates, which seem to have become a variable of high interest among several FOMC participants (no pun intended), have risen significantly, with the 10 year real yield at a level last seen since early 2019. The 2s10s yield curve measure has been inverted for a few days now. Lending standards across the board are tightening. Aggregate commodity prices are down 20% from their June peak, even including oil (to a lesser extent), reflecting expectations of weaker aggregate demand ahead.

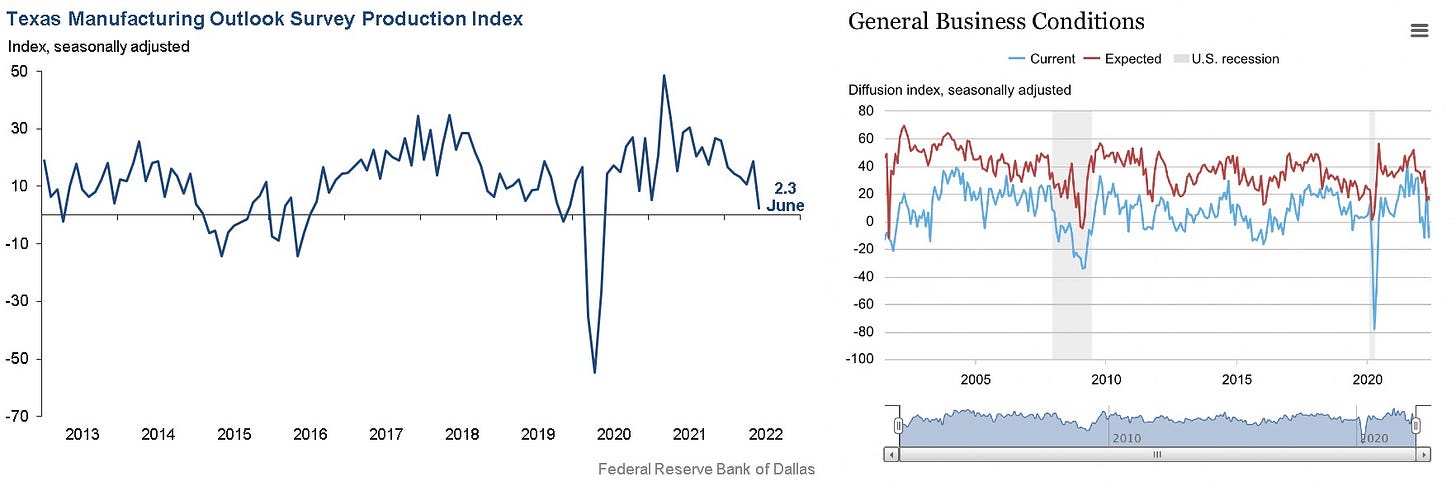

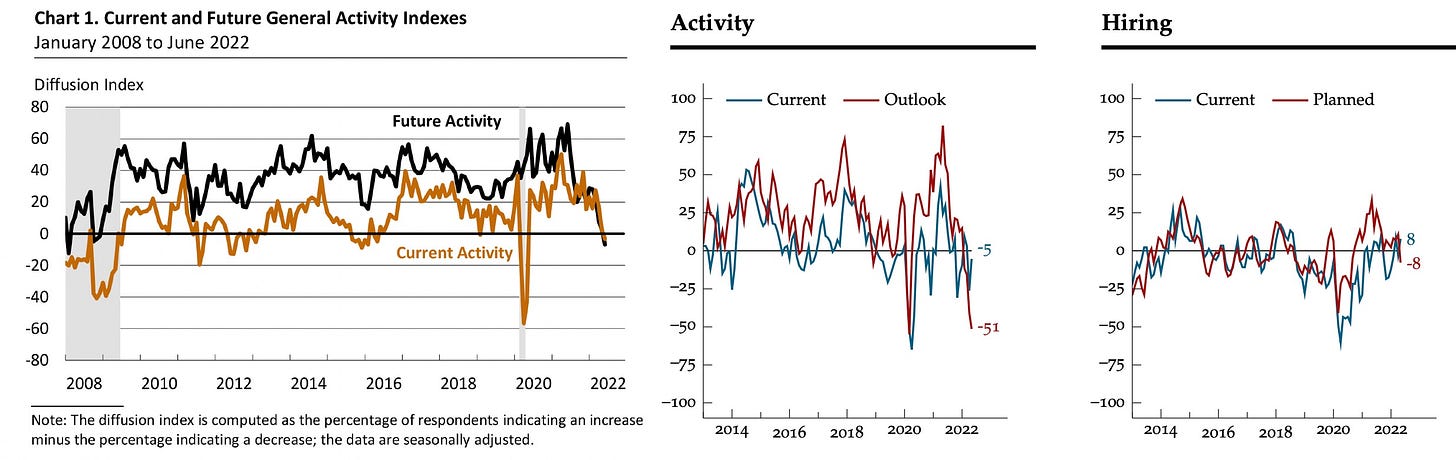

Investment seems to be waning. Orders for durable goods are slowing, as are those for nondefense, non-aircraft capital goods. Various regional Fed manufacturing surveys confirm that manufacturers expect a slowdown, with are already seeing early signs. The Philly Fed’s June survey saw 42% of regional manufacturers expecting their activity to slow down over the next six months (up from only 22% in May), with the first negative reading in their future activity index since December 2008. Kansas City’s survey saw respondents significantly cutting their predictions for orders, shipments, and even for employees and their work hours. The New York Fed’s Empire State Manufacturing Survey has seen several months of declines in both current and expected future conditions, as have Dallas’ and Richmond’s surveys.

Demand is also slowing in other industries, though not (yet) going red. The Richmond' Fed’s service sector survey saw continued softening last month; Dallas’ Texas survey saw solid current conditions but early signs and expectations of future slowing; New York’s was similar, though less rosy regarding the present.

Crucially, current demand reflects not only today’s demand shocks and interest rates, but also our expectations for them in the future. Mathematically, we can refer to how Clarida, Gali, and Gertler (1999) modeled the output gap (x_t below):

(What’s the Story)?

3I’ll attempt to summarize to conclude. The Fed does two things that matter the most:

It adjusts its administered policy interest rates, which in turn adjust the availability and cost of credit, asset prices, and risk taking (among other things). We can think of this as monetary policy’s “front-end” impact.

It sets the expected future paths of its administered policy rates, which in turn influence investment decisions, longer-term borrowing costs, and the expected level of demand in the near- and medium-term future (among other things). This is a sort of “back-end” impact, but it also feeds back into the front-end, especially through demand expectations (lower expected future incomes → scarcer and more expensive credit).

The Fed’s recent rate hikes have tightened financial conditions on the front-end, while Fed communication and forward guidance has led to expectations that these tight financial conditions will be around for some time and will only get tighter. This has hit expected demand, which discourages investment; less investment means slower employment growth and thus weaker nominal income growth expectations; thus current financial conditions tighten from the back-end, too.

My concern is that the Fed will pursue a policy path that pushes nominal income growth expectations to levels that lead to a recession through the chain-reaction process described above. In other words, I worry they will set and project interest rates that are overly inhibitive on economic activity through tight financial conditions as a result of relatively high policy rates and lower nominal income growth expectations. Financial conditions are already quickly tightening—the Chicago Fed’s [Adjusted] National Financial Conditions Index is at its highest (tightest) level since 2012.4

I am not saying the Fed shouldn’t raise rates, or that rate hikes are not currently appropriate. Hikes are appropriate—just probably not in their current size or pacing. To sound like Scott Sumner, the Fed should be following a policy path that markets believe will lead us to safety. The problem is that the Fed is not doing that—markets anticipate storms ahead. Using problematic indicators in a vague and open-ended framework is putting the Fed at risk of making policy decisions that could push us into that recession-inducing feedback loop of ever-tightening financial conditions (à la 2007-2008, but certainly not as bad).

To set better policy, the Fed needs to better read the room. But in these truly crazy times, getting policy right will always be difficult, no matter what. As Chair Powell said last Wednesday,

“We think that there are pathways for us to achieve the path back to 2% inflation while still retaining a strong labor market. We believe we can do that […] [but] there’s no guarantee that we can do that.”

Concerning the risk that the Fed tightens too far, Powell said that he “wouldn’t agree that it’s the biggest risk to the economy.” Alas, Chair Powell: you and I disagree!

I am referring only to consumer surveys here. Market-based measures of inflation expectations, which are almost always a better read of “inflation expectations”, are in great shape.

If you know the classic hardcore album whose title I’m referencing here, you’re the best

This unnecessary second album title reference goes out to the Brits.

The adjusted index better controls for correlation with GDP; also, conditions were technically tighter during the onset of the pandemic, but this was not for policy reasons.